Chapter Three |

|

My country, 'tis for thee,

My native country, thee,

Our father's God to Thee, |

Perhaps the largest event took place in Parkersburg, where a woman suffrage group had formed only six months earlier. Originally planned for May 2, the rally was moved to May 1. In the absence of the president of the local group, Cora (aka Cara) Ebert, Clarabel McNeilan presided. The meeting began with those present singing a suffrage song to the tune of "America," likely the same one recently adopted by the National American Woman Suffrage Association and distributed across the country in advance of the demonstrations. Doris Stevens, National Secretary of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, a more radical organization than the National American Woman Suffrage Association with which it had severed connection at the end of 1913 and one that emphasized passage of a federal suffrage resolution, was one of the speakers. Parkersburg native Hunter H. Moss, who was elected to Congress in 1912, and Governor Henry Hatfield were scheduled to speak, but Hatfield was unable to attend due to the mine disaster at Eccles three days earlier. Moss attended, giving, according to Clarabel McNeilan, who introduced him, "his first real suffrage speech." (Parkersburg Sentinel, May 2, 1914) "You may tell me that the permission I have to vote is not a right, but a privilege," Moss stated. "I admit it. But, when the law gives me that permission, then I say without fear of successful contradication, that a just law must also give to my sister of lawful age that same privilege . . . ." |  Hunter Moss, ca. 1913. West Virginia and Its People by Thomas Condit Miller and Hu Maxwell, 1913 |

|

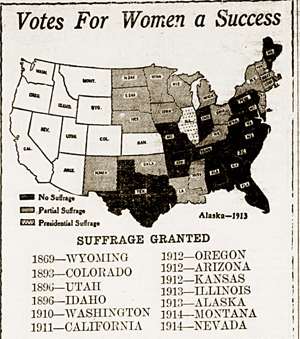

"We, the citizens of Parkersburg, have assembled today to voice our demands that women, as citizens of the United States, be accorded the full right of such citizenship. We congratulate the four million women voters who have won their right to the ballot in ten states, and confidentially expect to see five more states under the franchise banner after the November elections.

We hereby declare that suffrage for women has become a national, as well as a social issue, and we urge our Senators and Representatives to Congress to enact legislation which will insure to women political equal rights with men.

We, therefore ask the Congress of the United States to proceed without delay in the most feasible and practical manner to remove the barriers which prevent American women from the exercise of full franchise, and to make our country not a government in which half the people are denied the right of participation, but in truth and reality a democracy.

The above and foregoing is a true and correct copy of a resolution passed at a mass meeting held at Parkersburg this 1st day of May, 1914." |

Cara Ebert. Wheeling Intelligencer, May 1, 1916 |

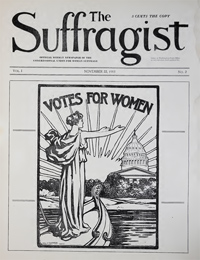

On June 5, Moss and fellow Congressman Matthew M. Neely accompanied a delegation of women from West Virginia, including Clarabel McNeilan of Parkersburg, to Capitol Hill to visit the chairman of the House Rules Committee and persuade him to let a suffrage bill be considered by the House of Representatives. At the end of July, suffragists met in Parkersburg to implement a re-organization of the state suffrage organization. In April, a committee of three Parkersburg women had been appointed to draft a plan, and the plan was presented at the July 30 meeting. In a shift in leadership away from the previous domination by Wheeling and Fairmont women, Cora/Cara Ebert of Parkersburg was elected president of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, Lenna Lowe Yost of Morgantown vice president, Daisy Peadro of Parkersburg corresponding secretary, Harriet Schroeder of Grafton recording secretary, and Carrie Zane of Wheeling treasurer. The association set a goal of getting the state legislature to decide in 1915 to present woman suffrage to the voters in 1916. |  Cover of The Suffragist, November 22, 1913. Publication of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. https://archive.org/details/thesuffragist |

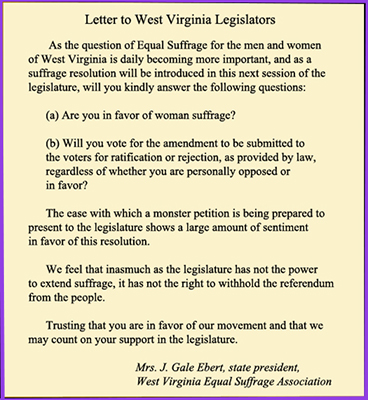

In November, on the heels of the mid-term elections that had brought full suffrage to women in only two more states, Cara Ebert wrote a letter, which the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association sent to members of the West Virginia State Legislature:

Ida Craft of New York came to West Virginia to assist with the campaign and spoke at several locations around the state. In January 1915, the Charleston Equal Suffrage Association established headquarters in the Holley Hotel for the legislative session. Woman suffrage supporters received a national setback when the U.S. House of Representatives defeated a suffrage resolution on January 12. The West Virginia delegation largely supported the measure, however, with Howard Sutherland, Mathew Neely, S. B. Avis, and James Hughes voting for it, William G. Brown Jr. (who, ironically, had married Izetta Jewell Kenney) voting against, and Hunter Moss not voting. In Charleston, Governor Henry Hatfield's biennial message was submitted to the West Virginia Legislature the following day, with a renewal of his support for woman suffrage. A week later, a proposed state amendment was introduced in the House by Delegate Michael Duty (Ritchie County) and in the Senate by Senator Noah Keim (Randolph County), both Republicans.

The West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association's legislative committee, headed by Lenna Lowe Yost of Morgantown, wife of Delegate Ellis Yost, actively promoted the legislation. Legislators also received petitions from several counties, in particular those in northern and central parts of the state.

| On January 26, women filled the Senate gallery and the outer room for the Senate vote on the resolution. Senators voted 28 for, 1 against, with 1 absent. Delegates followed suit soon after, although the process proved a violation of the rules and they had to vote again another day. The final vote was 77 for the resolution, 5 against, and 3 absent. Undercurrents of opposition were evident, however, in the remarks of legislators such as Senators Garnett K. Kump of Hampshire and Benjamin L. Rosenbloom of Ohio. Both men voted for the resolution, but neither supported woman suffrage. A loyal Democrat, Kump voted in line with the decision of the party at its convention in 1914 to support submitting woman suffrage to the people. Rosenbloom, a Republican, made his intentions clear when he stated, "I will vote against it at the polls and do all I can to defeat its adoption." (Parkersburg News, January 27, 1915) |

"However we may feel, as individuals, we must all congratulate the equal suffragists of West Virginia, not only upon this preliminary victory, but upon the clean, attractive and dignified manner in which they have conducted their propaganda. And after all is said and done, if the illiterates, drunkards, wardheelers and gamblers can help decide the questions of statecraft, why not the noble, clean-souled women of the commonwealth, who must rear its children and furnish the inspiration for its highest ideals." - The Charleston Gazette, January 28, 1915 |

Primary Documents:

Hunter H. Moss Address at Suffrage Rally, 1914West Virginia Delegation, by Clarabel J. McNeilan, 1914

West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association Plan of Organization, 1914

West Virginia Senate Joint Resolution on Suffrage Amendment, 1915

Remarks of WV Senator G. K. Kump on Suffrage Amendment, 1915