Chapter Six

Ratification of the 19th Amendment

|

"I am not only in favor of ratifying the National Suffrage Amendment but am urging the governor to call the legislature in a special session for that purpose."

- Sen. Harvey W. Harmer, The West Virginian, July 17, 1919

|

Adoption of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment required ratification by thirty-six states. By the end of June 1919, nine states had ratified the amendment, and another thirteen followed suit before the end of the year. In West Virginia, less than two weeks after Congress approved the federal amendment, a committee of Fairmont women asked Governor John Cornwell to call a special session of the West Virginia Legislature to ratify it. At the same time, some legislators urged the governor to call a special session, among them longtime supporter Harvey Harmer of Clarksburg who had first introduced a suffrage resolution in the West Virginia Legislature in 1895. The governor declined to take action during the summer or fall months, however, in part because the legislature recently had met in special session on another matter but also because woman suffrage had been so soundly defeated in West Virginia just three years earlier. |

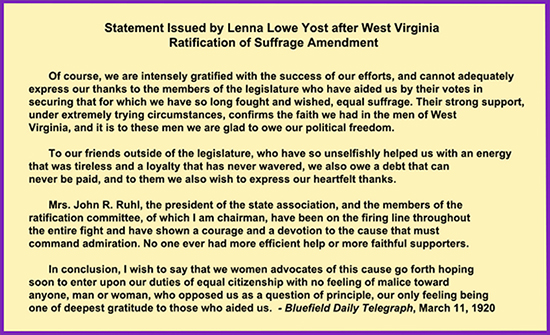

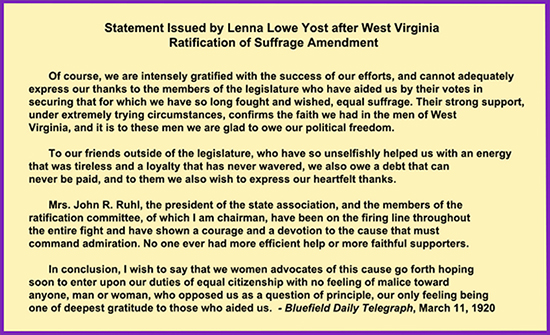

| The West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association (WVESA) was cautious about pressuring the governor but worked to garner support among a sufficient number of legislators to win ratification when a special session was called. While Julia Ruhl continued as president of the WVESA, Lenna Lowe Yost became chair of the ratification committee. An advisory board, comprised of dozens of men and women from around the state, was formed. Yost invited not only people who urged a conservative approach but also women such as Florence Hoge and Izetta Jewell Brown, whose affiliation with the National Woman's Party revealed a more aggressive approach, to join the advisory board. Over the summer, suffragists began circulating petitions in favor of ratification. Yost also corresponded with legislators and other political leaders as the months passed and even enlisted the help of several to persuade those had not made a decision as to how they would vote. Both the WVESA and the National Woman's Party polled legislators to determine their position on the woman suffrage amendment, and results indicated majorities in both houses. |

Lenna Lowe Yost, Progressive West Virginians, 1923 |

Woman Suffrage Amendment, National Archives |

By the end of 1919, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) leaders were increasingly anxious for the West Virginia governor to call a special session. The NAWSA wanted ratification of the amendment in time for women to vote in the 1920 presidential election, and in late December Carrie Chapman Catt urged Governor Cornwell to act. Cornwell was awaiting a court decision in a lawsuit over an oil and gas tax approved by the state, which would determine whether a special session was needed on that issue. Yost, having a better understanding of the situation in West Virginia, was willing to wait longer, stating to the press in January 1920, "We are entirely satisfied with the governor's position." (Charleston Daily Mail, January 30, 1920) She did keep in communication with Governor Cornwell, however, letting him know how the vote was expected to go. Finally, on February 20, 1920, Cornwell issued the call for a special session to convene on February 27 to ratify the woman suffrage amendment as well as to consider several items.

As legislators assembled, members of the WVESA ratification committee and advisory board also arrived in Charleston. Emphasizing that the WVESA had not shown favoritism to Democrats or Republicans, Yost stated, "We are making a straight-out fight for ratification and for nothing else. We are trying to make it honestly and without subterfuge or trickery, as we believe that this is the only kind of fight that should be made and the only kind of a fight that will win in the end, and we wish again to warn our friends to be on the lookout for all kinds of rumors that may be started solely for the purpose of affecting votes in the legislature." (The Charleston Gazette, March 1, 1920)

|

| In his message to the legislature, Cornwell commented:

Confronted, as we are, by the statute requiring the county courts to convene the first Monday in March to set in motion the machinery for registering the voters; confronted with the certainty of the Equal Suffrage Amendment to the Federal Constitution being ratified before the general election, regardless of the action or the non-action of West Virginia, it was apparent that if the male voters were registered, under our present system, and there was no registration of the women voters, a special session to amend the registration law would be inevitable later and a second registration would be necessary, causing a great deal of extra expense and confusion. Then, it goes without saying that the women should be admitted into the primaries and allowed to participate in the nomination of candidates. To be given the privilege of voting for candidates after they are nominated but denied the right to participate in the nomination of the candidates would be an anomalous situation.

In addition to all this, the women of the state, who favor suffrage for their sex, very naturally and very properly feel that they want the men of West Virginia to participate in their enfranchisement and they would feel humiliated at the thought of suffrage being extended to them by the men of other states, solely, without the aid or assistance of the men of their own state. Both of the larger political parties are committed to the suffrage amendment through their platform declarations, as well as through the utterances of their national leaders, consequently it is in no sense a partisan question, but is one upon which members of both parties can unite. (Journal of the Senate, 1920) |

John J. Cornwell, West Virginia State Archives |

WVESA Ratification Committee (Henrietta Romine, Cora Ebert, Julia Ruhl, Nancy Mann, Daisy Peadro, and Lenna Lowe Yost) with petitions for ratification. Huntington Advertiser, September 26, 1920 |

Senator Harvey Harmer, who had requested the privilege, offered the woman suffrage resolution in the Senate on the first day of the session, while Delegate William S. John of Monongalia County, offered it in the House of Delegates. The next day, opponents in both houses introduced a resolution rejecting the proposed amendment. In addition, both a resolution and a bill were presented in the House that would submit to the voters of West Virginia a state amendment granting voting rights to women. A similar bill was introduced in the Senate. Legislators in both bodies presented numerous petitions, telegrams, and other communications for or against ratification of the woman suffrage amendment. The WVESA Ratification Committee submitted pro-ratification petitions with thousands of signatures. |

|

"It will be one proud day to the Piedmont Civic Club when there is flashed over the wires the news that the Anthony Amendment has been ratified by the West Virginia Legislature."

- Nan K. Hepburn, President

|

"We ask you to vote against Woman Suffrage because an overwhelming majority of West Virginia voters cast their ballot against equal suffrage . . . ."

- A. F. Francis and wife, et al, residents of Moundsville

|

On March 3, the House voted 47 to 40 to ratify the woman suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Among those voting against ratification was Delegate Tol Neale of Cabell County, who remarked, "I am perfectly willing if it can be done to submit this question to the voters of West Virginia for ratification or rejection, but I am not willing to say that the ninety-eight thousand and sixty-seven voters of the state of West Virginia, by their votes cast less than four years ago, have all been converted to woman suffrage." Neale continued, "I can see the radical element in the next few years filling our senate and congress chambers at Washington; then and not until then will the American people realize just what the Democratic and the and the [sic] Republican national committee have done by endorsing and working for woman suffrage." (Journal of the House, 1920) The affirmative vote of the House did not settle the matter for all members, a few of whom still attempted over the days that followed to have the body consider legislation sending the matter to the voters or to reconsider the vote of March 3. In that body, Delegate John kept delegates from taking such action and also had to overcome attempts to adjourn sine die, an action that would have defeated woman suffrage in light of what was happening in the Senate.

Harvey W. Harmer, Progressive West Virginians, 1923 |

Meanwhile, the Senate was the scene of much suspense. On March 1, the Senate voted 14-14 on the resolution, but before the vote was verified Senator Harmer changed his vote to "No" in order that he would have the privilege of moving for a reconsideration later. Two senators, Jesse Bloch of Ohio County and A. R. Montgomery Jr., formerly of Logan County, were not present when the vote was taken. Senator Montgomery had resigned his seat the previous summer when he decided to move to Illinois, a fact that would become part of the saga over woman suffrage and the West Virginia Senate. Senator Bloch, who supported woman suffrage, was in California when the special session was called and sent a telegram to Harmer on the 1st to ask his vote be paired with another senator, a courtesy of pairing opposing votes of members when a member was not present. None of the opponents would be paired, and Bloch responded to a plea for his appearance at the session by setting out from Pasadena to Charleston. While he journeyed by train, Harvey Harmer in particular worked to keep the Senate gaveling into session each day, not taking any action that might make Bloch's pending arrival moot, and adjourning until the next scheduled day. At the same time, Democratic and Republican leaders tried to persuade anti-suffrage legislators to change their minds: It was reported that President Woodrow Wilson even sent telegrams to two Democratic senators in an attempt to bring ratification. |

Jesse Bloch, Who's Who in West Virginia, 1916 |

|

|

It took Senator Bloch five days to reach Charleston, with news reporting his passage through places such as Albuquerque, New Mexico; Grand Canyon, Colorado; Chicago, Illinois; and Cincinnati, Ohio, en route to the state capital. In Chicago, he had the option of flying by airplane or taking a special train from Chicago to Cincinnati, and, taking the train, he arrived in Charleston early on the morning of March 10. That day, the Senate voted on the federal amendment, ratifying it by a vote of 16 to 13 and making West Virginia the 34th state to ratify the Susan B. Anthony Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

|

Senator Edgar B. Stewart (Monongalia), NWP organizer Mary Dubrow, Senator Jesse Bloch, and NWP worker Betty Gram, The Suffragist, April 1920

|

"I am glad that I will have the pleasure of casting my vote for the suffrage amendment and also to praise the fourteen fellow members of the senate who have stood together solidly to hold the special session together until my arrival. It is they that deserve the credit for any good that may come of my vote, because it was only the courageous stand taken by them that made it possible for my ballot to be counted."

- Sen. Jesse A. Bloch, The Charleston Gazette, March 10, 1920

|

Before the legislature adjourned on March 11, Delegate John introduced two bills for implementation of woman suffrage in West Virginia, but members were more inclined to end the special session than discuss additional legislation. John made a statement that would prove prescient:

I desire to state upon the record that House Bill No. 14 to effectuate the nineteenth amendment to the United States constitution in case it becomes operative by ratification by thirty-six states and House Bill No. 15 to provide for the registration of women in the same event and at the time of the registration of male citizens, were introduced not because I regard them as essential to the right of women to vote in the event the nineteenth amendment is ratified and becomes effective, but as prudent and precautionary measures. I introduced them as an offer of appropriate legislation relating to the nineteenth amendment, as that subject is embraced in the Governor�s call. They are offered in the endeavor to do all that is necessary to make the nineteenth amendment effective without another special session of this legislature. I trust we shall never find that such legislation is essential for that purpose.

The test votes on House Bill No. 14 on the motion to dispense with reference to a committee and also to order the bill printed, show that it is useless to press them for passage at this time, and that we could not secure the necessary majority to make them effective within ninety days if passed.

The State of Washington ratified the Anthony Amendment less than two weeks after West Virginia. Winning the final state proved difficult as Spring passed into Summer before Tennessee narrowly became the 36th state to ratify woman suffrage on August 18, 1920. On August 26, the United States Secretary of State certified the amendment as part of the U.S. Constitution.

Although the legislature had ratified the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, the issue was not settled for West Virginia. Over the summer, the American Constitutional League, a group of anti-suffrage men, filed a court challenge in the District of Columbia to ratification of the amendment in several states, including West Virginia. Regarding West Virginia, the case asserted that the Senate had violated its own rules, thus making ratification illegal. West Virginia's ratification also was raised as an issue in a Maryland case over the amendment, Leser et al v. Garnett et al. Not until 1922, when Justice Louis Brandeis wrote an opinion for the United States Supreme Court in the case that upheld ratification of the 19th Amendment, and addressed the issue contended in of West Virginia, was the matter fully resolved.

Primary Documents:

"The Story of Ratification by West Virginia," by Julia Ruhl, 1920

"Fourteen to Fourteen," by Mary Dubrow, 1920

Select Communications Sent to the Senate on the Woman Suffrage Amendment, 1920

"Suffrage Failure Big Disappointment," 1920

Remarks from Senators on Woman Suffrage, 1920

Speech of Delegate J. S. Thurmond on Woman Suffrage, 1920

Legislative Vote on the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment, 1920

"The Long, Long Ride of Senator Bloch," 1920

"By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them," 1920

Previous Chapter |

Next Chapter

|