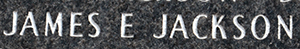

James Edward Mason Jackson was born in Jefferson County, West Virginia, on June 21, 1913, to Augustus (spelled "Agustus" in various family documents, including his will) Jackson (1879-1930) and Elizabeth ("Bettie") Doleman Jackson (1879-1958). Per the 1910 Federal Census, his older siblings included Louise (b. 1900), Lora (b. 1902), "Gussie" (b. 1903), and Bessie (b. 1905). In 1920 his siblings included Loretta (b. 1910), Charles Rudolph (b. 1915), John Ernest (b. 1918), and later Parthenia Beatrice (b. 1922), and Dorothy V. (b. 1923). Additionally, the father's will lists the surviving children as heirs, and James Jackson and his siblings are listed in his younger brother John E. Jackson's obituary in December 2000.

Jackson registered for the draft on October 16, 1940. His father had died in 1930, and Jackson lists his mother as next-of-kin on his draft registration card. The surname of his mother is shown as Durbin. They are living in Washington, D.C., and he is employed by Bertha E. Farwell. His draft card lists him as age 27, head of household, and his mother as a member living in the household. He is described as "light brown," height as 5' 9", and weight as 145. He signs his name as James Edward Mason Jackson.

Jackson became a Navy man (seaman second class), and it is in this role that his story becomes an important piece of U.S. history. On July 17, 1944, James E. M. Jackson became a victim of the catastrophic Port Chicago Naval Magazine Explosion. Jackson had been in the service for two years and had been "marrid" on the Pacific coast since entering the service (Spirit of Jefferson, July 21, 1944). Port Chicago was a naval magazine and barracks located on the Suisan Bay, at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers northeast of the San Francisco Bay. Following is a summary of the disaster from the Naval History and Heritage Command:

America was swept into World War II on 7 December 1941. As war in the Pacific expanded, the Naval Ammunition Depot at Mare Island, California, was unable to keep up with the demand for ammunition. Port Chicago, California, located 35 miles north of San Francisco, proved an ideal place for the Navy to expand its munitions facilities.

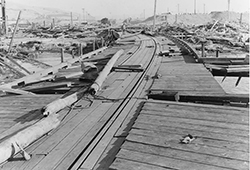

Port Chicago Sailors. Photo courtesy National Park Service

|

Construction at Port Chicago began in 1942. By 1944, expansion and improvements to the pier could support the loading of two ships simultaneously. African-American Navy personnel units were assigned to the dangerous work at Port Chicago. Reflecting the racial segregation of the day, the officers of these units were white. The officers and men had received some training in cargo handling, but not in loading munitions. The bulk of their experience came from hands-on experience. Loading went on around the clock. The Navy ordered that proper regulations for working with munitions be followed. But due to tight schedules at the new facility, deviations from these safety standards occurred. A sense of competition developed for the most tonnage loaded in an eight-hour shift. As it helped to speed loading, competition was often encouraged. |

On the evening of 17 July 1944, the empty merchant ship SS Quinault Victory was prepared for loading on her maiden voyage. The SS E.A. Bryan, another merchant ship, had just returned from her first voyage and was loading across the platform from Quinault Victory. The holds were packed with high explosive and incendiary bombs, depth charges, and ammunition--4,606 tons of ammunition in all. There were sixteen rail cars on the pier with another 429 tons. Working in the area were 320 cargo handlers, crewmen and sailors.

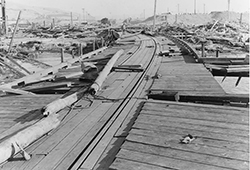

At 10:18 p.m., a hollow ring and the sound of splintering wood erupted from the pier, followed by an explosion that ripped apart the night sky. Witnesses said that a brilliant white flash shot into the air, accompanied by a loud, sharp report. A column of smoke billowed from the pier, and fire glowed orange and yellow. Flashing like fireworks, smaller explosions went off in the cloud as it rose. Within six seconds, a deeper explosion erupted as the contents of the E.A. Bryan detonated in one massive explosion. The seismic shock wave was felt as far away as Boulder City, Nevada. The E.A. Bryan and the structures around the pier were completely disintegrated.

A pillar of fire and smoke stretched over two miles into the sky above Port Chicago. The largest remaining pieces of the 7,200-ton ship were the size of a suitcase. A plane flying at 9,000 feet reported seeing chunks of white-hot metal "as big as a house" flying past. The shattered Quinault Victory was spun into the air. Witnesses reported seeing a 200-foot column on which rode the bow of the ship, its mast still attached. Its remains crashed back into the bay 500 feet away.

| All 320 men on duty that night were killed instantly. The blast smashed buildings and rail cars near the pier and damaged every building in Port Chicago. People on the base and in town were sent flying or were sprayed with splinters of glass and other debris. The air filled with the sharp cracks and dull thuds of smoldering metal and unexploded shells as they showered back to earth as far as two miles away. The blast caused damage 48 miles across the Bay in San Francisco. |

This view looks south from the munitions pier, showing the wreckage of Building A-7 (Joiner Shop) at the right. There is a piece of twisted steel plating just to the left of the long pole in the left center. Photo was taken by the Mare Island Navy Yard (NH 96821).

|

Navy personnel quickly responded to the disaster. Men risked their lives to put out fires that threatened nearby munitions cars. Local emergency crews and civilians rushed to help. In addition to those killed, there were 390 wounded. These people were evacuated and treated, and those who remained were left with the gruesome task of cleaning up.

Less than a month after the worst home-front disaster of World War II, Port Chicago was again moving munitions to the troops in the Pacific. The men of Port Chicago were vital to the success of the war. And yet they were often forgotten. Of the 320 men killed in the explosion, 202 were the African-American enlisted men who were assigned the dangerous duty of loading the ships. The explosion at Port Chicago accounted for fifteen percent of all African-American casualties of World War II.

The Armed Forces were a mirror of American society at the time, reflecting the cooperation and dedication of a country. For many people, the explosion on 17 July 1944, became a symbol of what was wrong with American society. The consequences of the explosion would begin to reshape the way the Navy and society thought about our social standards. More importantly, the explosion illustrated the need to prevent another tragedy like this one.

The tremendous danger and importance of the work, while not always recognized by the public, was always present in the minds of the men of Port Chicago. The Marines, Coast Guard, and civilian employees knew of the danger, but none as vividly as the Merchant Marine crew and the Naval Armed Guard of the ships and the men serving on the loading docks.

In 1944, the Navy did not have a clear definition of how munitions should best be loaded. The dangerous work on the piers at Port Chicago and other Navy facilities was done by the men of the ordnance battalions. These men, like their officers, had received very little training in cargo handling, let alone working with high explosives.

Coast Guard instructions, published in 1943, were often violated as it was felt that they were not safe or fast enough for Port Chicago's specific circumstances. The men on the pier were experimenting with and developing procedures which they felt were safer and faster.

After the explosion, the Navy would institute a number of changes in munitions handling procedure. Formalized training would be an important element, and certification would be required before a loader was allowed on the docks. The munitions themselves would be redesigned for safety while loading.

Port Chicago would also lead people to examine their society. There was growing resentment toward the policies of racial segregation throughout the nation. The Navy opened its ranks to African-Americans in 1942, but men served in segregated units supervised by white officers, and opportunities for advancement were extremely limited. The men assigned to the ordnance battalion were African American.

The explosion had shaken all of the men, but especially those surviving men who worked on the pier. Of the 320 men killed, almost two-thirds were African-American from the ordnance battalion. What had been minor grievances and problems before the explosion began to boil as apprehension of returning to the piers grew. On 9 August, less than one month after the explosion, the surviving men, who had experienced the horror, were to begin loading munitions, this time at Mare Island. They told their officers that they would obey any other order, but not that one.

Of the 328 men of the ordnance battalion, 258 African-American sailors refused to load ammunition. In the end, 208 faced summary courts-martial and were sentenced to bad conduct discharges and the forfeit of three month's pay for disobeying orders. The remaining 50 were singled out for general courts martial on the grounds of mutiny. The sentence could have been death, but they received between eight and fifteen years at hard labor after a trial which a 1994 review noted had strong racial overtones. Soon after the war, in January 1946, all of the men were given clemency. [On 23 December 1999, Freddie Meeks of Los Angeles, one of the few still living members of the "Port Chicago 50" received a presidential pardon. To date, complete exoneration of all 50 Sailors has not occurred.]

The explosion and later mutiny proceedings would help illustrate the costs of racial discrimination and fuel public criticism. By 1945, as the Navy worked toward desegregation, some mixed units appeared. When President Harry Truman called for the Armed Forces to be desegregated in 1948, the Navy could honestly say that Port Chicago had been a very important step in that process.

Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial is administered by the National Park Service and the United States Navy. It honors the memory of those who gave their lives and were injured in the explosion on 17 July 1944, recognizes those who served at the magazine, and commemorates the role of the facility during World War II. [In October 2009, the Defense Authorization Act was signed, designating the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial as a unit under the National Park Service.] ("Port Chicago Naval Magazine Explosion, 1944," 20 November 2017, accessed 28 September 2021, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/p/port-chicago-ca-explosion.html.)

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be

provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant

personal history.