Courtesy Cynthia Mullens

Remember...

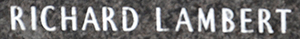

Richard J. Lambert

1920-1942

"When you go home

Tell them of us, and say

For your tomorrow,

We gave our today."

Patrick O'Donnell

Courtesy Cynthia Mullens |

Remember...Richard J. Lambert

|

Richard J. Lambert was born on August 1, 1920, at Whitmer, Randolph County, West Virginia, to Stella Mullennex Lambert and Hugh Lambert of Elkins.

In 1910, Mr. and Mrs. Lambert lived with Mrs. Lambert's parents and her brothers and sisters in Dry Fork of Randolph County. It was the year of their marriage. Mr. Lambert was a laborer on the farm. Mrs. Lambert's son from a previous relationship was not recorded by the census taker to be in the household. In 1920, the census taker found Mr. and Mrs. Lambert in their own home in Dry Fork, among family. Mullennex families were recorded to be in the same neighborhood. In Hugh Lambert's household were Stella and children Hansel Rossey, Myrtle, Buel, and Pearl. Richard was born later in the year, several months after the census was recorded. In 1930, the family was found in Calhoun County. Mr. Lambert was working in road construction, and Mrs. Lambert was a keeper in their boarding house. With them were Buel, Pearl, Richard, and Myrtle, now married to Charles Collins. There were five boarders in their home.

Mr. Lambert died in 1938. By that time, he had returned to Elkins and died in the hospital there. He was buried in Maplewood Cemetery in Elkins. In 1940, Mrs. Lambert appears in the census records, living near Elkins as the head of the household with her daughter Pearl Lambert, who was working as a wrapper in a bakery. Myrtle and her husband and children were also living there.

Richard Lambert was not recorded to have been in the household, but it appears that he'd joined the U.S. Army in 1939, after two years of college. Richard Lambert was placed with the Army Air Corps in the 28th Bombardment Squadron. In the Philippine Islands on Luzon, the 28th was stationed at Clark Airfield.

The U. S. had been building up a presence on Luzon during 1941 in anticipation of the need to contain Japan. The Philippine Islands would serve a strategic need for either side. Clark Airfield was holding a very large contingent of planes in December 1941.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japanese forces. Nine hours after Pearl Harbor was hit, Clark Airfield was attacked. Most of the planes were destroyed on the ground. In January 1942, Clark Airfield was overrun by Japanese forces.

U. S. and Philippine forces retreated to the Bataan Peninsula to escape the Japanese. The retreat was a series of strategic moves toward the peninsula that were ultimately successful but just so. Once in place, they were trapped on the peninsula with no support. Still, they were able to hold out for three months, but as the months wore on, the soldiers were overcome with disease and starvation. General [Edward] King surrendered to Japan on April 9, 1941, and Japan claimed approximately 75,000 troops. ("Bataan Death March," History.com, 9 November 2009, 7 June 2019, accessed 19 April 2020, https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/bataan-death-march and "Clark Air Base," Wikipedia, accessed 19 April 2020 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clark_Air_Base.)

What followed became known as the Bataan Death March. The troops were gathered and captured and forced to march 65 miles from the southern end of Bataan to San Fernando. The health of many of the men was already compromised by disease, injury, and starvation, and the treatment they received was cruel. Many were outright killed if they were unable to walk or didn't obey orders. Some were executed as an example to others. Estimates of deaths are as high as 10,000 on the way to San Fernando. (Ashley N. McCall, "Surrender at Bataan Led to One of the Worst Atrocities in Modern Warfare," USO, 14 November 2015, accessed 19 April 2020, https://www.uso.org/stories/122-surrender-at-bataan-led-to-one-of-the-worst-atrocities-in-modern-warfare.) Those who survived the five-day march were loaded into railway cars and taken to prisoner-of-war camps.

Richard Lambert was among those who survived the Bataan Death March. The first report of his capture was May 7, 1942.

According the official government account,

Following the Allied surrender on the Bataan Peninsula on April 9, 1942, the Japanese began the forcible transfer of American and Filipino prisoners of war to various prison camps in central Luzon, which sits at the northern end of the Philippines. The largest of these camps was the notorious Cabanatuan Prison Camp, which at its peak held approximately 8,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war captured during and after the Fall of Bataan. Camp overcrowding worsened with the arrival of Allied prisoners who surrendered from Corregidor on May 6, 1942. Conditions at the camp were poor and supplies of food and water extremely limited, leading to widespread malnutrition and outbreaks of malaria and dysentery. By the time the camp was liberated in early 1945, approximately 2,800 Americans had died at Cabanatuan. Prisoners were forced to bury the dead in makeshift communal graves that were often completed without records or markers. As a result, identifying and recovering remains interred at Cabanatuan proved exceedingly difficult in the years after the war.Sergeant Richard Lambert joined the U.S. Army Air Forces from West Virginia and was a member of Headquarters Squadron of the Far East Air Force in the Philippines during World War II. He was captured in Bataan following the American surrender on April 9, 1942, and died of dysentery on October 12, 1942, at the Cabanatuan Prison Camp in Nueva Ecija Province. He was buried in a communal grave in the camp cemetery along with other deceased American POWs; however, his remains could not be associated with any remains recovered from Cabanatuan after the war. Today, Sergeant Lambert is memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines. ("SGT Richard Lambert," Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, accessed 19 April 2020, https://dpaa.secure.force.com/dpaaProfile?id=a0Jt0000000LlNaEAK.)

The American Battle Monuments Commission continues to list Richard Lambert as missing in action.

Article prepared by Cynthia Mullens

August 2020

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant personal history.