Courtesy Cynthia Mullens

Remember...

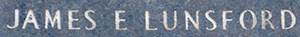

James E. Lunsford

1932-1951

"He died on the field of battle. It was noble thus to die."

�Inscription on the headstone of Pvt. James E. Lunsford

Courtesy Cynthia Mullens |

Remember...James E. Lunsford

|

James E. Lunsford was born on August 24, 1932, to James Earl and Ruby May Graham Lunsford, near Elkins, Randolph County, West Virginia.

In the 1940 Federal Census, James Lunsford is listed as the grandson in the house of his maternal grandparents, Joe and Evalina Graham. Joe Graham was the manager and owner of a second-hand furniture store. In a separate household, James' parents, James and Ruby Lunsford, lived with their daughter Rosella (later known as Rose Ellen) and son Max and with lodgers Alford and Geraldine. James was a truck driver for Graham Transfer. Peter Lunsford was born in 1940 after the census for that year was counted.

Research did not reveal details of James Lunsford's early life. He picked up the nickname "Bunky," perhaps a reference to a cartoon published from 1926 through 1948 whose star was Bunky (Short for Bunker Hill Jr.), a baby alone in the world who went on adventures on his own. ("Barney Google and Snuffy Smith," Wikipedia, last edited 17 August 2020, accessed 19 August 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barney_Google_and_Snuffy_Smith#Bunky.) In publicly available records, he is next listed as Private Lunsford and was placed with the 24th Infantry Division, 19th Infantry Regiment, Company G. He enlisted in December 1950.

The 24th was part of an occupying force in Japan after World War II and had begun downsizing by 1950 when the Korean War began on June 25, 1950. ("A Summary History of the 24th Infantry Division: Victory Division," MilitaryVetShop.com, updated 22 September 2010, accessed 18 March 2020, http://www.militaryvetshop.com/History/24thInfantryDivision.html.) The 24th was among the first into Korea when the U.S. joined the conflict, understaffed and underequipped.

As described in an overview of the division's history, the goal of early fighting for the U.S. forces was to delay and hinder the North Korean forces until the United Nation forces could be deployed and the U.S. forces built. The delaying tactics worked, but at great cost. By July 16, 1950, the 24th was attempting to protect individual cities and strong positions but were overwhelmed by North Korea's numbers and tanks. ("A Summary History of the 24th Infantry Division.") However, they were successful in delaying the advance of North Korean troops and the delay gave South Korea enough time to settle its defenses around Pusan. United Nations forces tightened the defense from the Pusan Perimeter to the Naktong River by the end of July. By the end of August, the perimeter was all but secured. (William V. Schmitt et al., A Brief History of the 24th Infantry Division in Korea, 24th Division Information and Education Office, September 1956, accessed 19 August 2020, http://24thida.com/books/books/1956_brief_history_24th_division_Korea_OPT_SM.pdf.) The United Nations went on the offensive in September and began pushing back the enemy to the North.

As the United Nations forces approached the barrier between North and South Korea at the 38th Parallel, all eyes were on the Korean War. Would the United Nations forces cross into North Korea or re-enforce the agreement post-World War II on this line? By October, they decided to cross. The 24th was beyond Pyongyang, North Korea, in October and near the Yalu River (on the border between North Korea and China) in November, but China's entry into the war halted northward progress and forced a withdrawal that winter, all the way back to Seoul. In the spring, the 24th and U.N. forces pushed north again. On April 1, 1951, fighting was again north of the 38th parallel. The enemy was weakened by long supply lines and inferior equipment, though its numbers were superior to the Korean and U.N. forces.

By the time June 1951 ended, the war was said to be at a standstill, again stabilized near or on the 38th parallel.

The engravings on Private James Lunsford gravestone state that he was killed in action in Sungamni, Korea, on July 25, 1951. This is at a time when hostilities had been minimized and troops concentrated closer to the 38th Parallel, according to various online sources. The town of Sungamni, as it exists today, is near the east coast of North Korea, about 50 miles south of the border with China, well north of the 38th Parallel. An Elkins newspaper carried a burial announcement on December 8, 1951, indicating that he'd died in service to his country the preceding July, validating the date. The military headstone application says that he died in service.

Private Lunsford was awarded the Purple Heart, the Combat Infantryman's Badge, the Korean Service Medal, the United Nations Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Korean Presidential Unit Citation, and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal.

Article prepared by Cynthia Mullens

July 2020

West Virginia Archives and History welcomes any additional information that can be provided about these veterans, including photographs, family names, letters and other relevant personal history.