WVU: The First 50 of 150

by Christine M. Kreiser

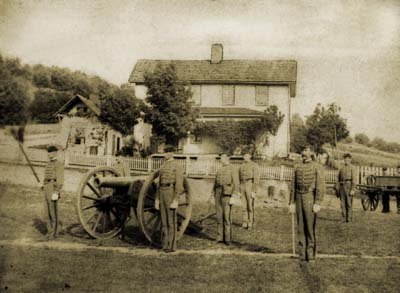

In one of the oldest known photos from WVU, the school's artillery cadets stand at attention in front of Fife Cottage in 1870.

Fife Cottage near the site of the future Woman's Hall. It was one of the earliest classroom facilities at WVU and was used frequently for science experiments.

“Knowledge is power,” wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1817. It is “safety,” and it is “happiness.”

OK, Jefferson borrowed the phrase from Francis Bacon. And the Virginia General Assembly roundly ignored his attempts to reform the state’s education system—reforms that (with the exception of free elementary education for girls) were meant almost solely for the young men who would one day run the Commonwealth. But you get the idea.

Jefferson’s crowning educational achievement, the University of Virginia, was intended to be free from the anti-Southern prejudices of Northern colleges—a “canker,” Jefferson explained in 1821, that was “eating on the vitals of our existence.” His university, in the heart of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains, would be fit for the sons of cavaliers.

West of the Blue Ridge, however, the sons of mountaineers showed little interest in Mr. Jefferson’s “academical village” in Charlottesville. Virginia’s parsimonious educational funding, in the words of a Harrison County judge in 1841, had been “frittered away in the endowment of an institution whose tendencies are essentially aristocratic and beneficial only to the very rich.” Just before the Civil War, more western Virginians were enrolled in Northern colleges than in all the Virginia colleges east of the Blue Ridge.

But West Virginians moved quickly to rectify matters after achieving statehood on June 20, 1863. A year earlier, President Abraham Lincoln had signed into law the Morrill Act, which allowed states to fund public colleges from the sale of public lands. These land-grant colleges would focus on agriculture and the mechanic arts. After all, with large swaths of western land coming under the plow and the country in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, farms and factories were America’s future.

But where to put this new institution? Two years after the Civil War, North-South divisions still ran deep in the Mountain State, which had not yet settled on a permanent capital. Wheeling, Clarksburg, Parkersburg, and Charleston had their sights set on hosting the seat of state government, so they took themselves out of the running for the college. Moundsville—home to the state penitentiary—and Weston—site of the state asylum—turned it down, preferring the economic certainties provided by their respective inmates to the unpredictability of a bunch of transient students.

Small rural communities in every corner of West Virginia vied for the new school. In the end, the offer of $51,000 worth of property in Monongalia County no doubt helped the state legislature reach its final decision. On February 7, 1867, the Agricultural College of West Virginia officially found its home in Morgantown, just miles from the Pennsylvania border. If that rankled southern West Virginians, they got some vindication two years later when Charleston was named the capital city. (West Virginia’s “floating capital” would return to Wheeling in 1875, before moving permanently to Charleston in 1885.)

Meanwhile, on the banks of the Monongahela River, the Rev. Alexander Martin presided over the state’s new land-grant college. Martin had grand ambitions for the school and lobbied early for a name change. In 1868, Martin told Governor Arthur Boreman to drop “the somewhat inconvenient word ‘Agricultural’ which makes some think it is only a Farmers School.” Boreman and the legislature agreed, and the erstwhile Agricultural College of West Virginia became West Virginia University.

Martin might have been on to something, but he was obligated by the Morrill Act to include agriculture in WVU’s curriculum. So, he asked for volunteers to till some soil. One of those volunteers, Marmaduke Dent, recalled the experiment in a 1901 article for the Monticola yearbook. To “keep faith with a generous Congress” by undertaking “something purely agricultural,” a group of young men went to work on 15-by-20-foot garden plots with varying degrees of expertise. “Some planted the seeds so deep that if they sprouted they could not reach the surface,” Dent recalled, “others so shallow that they might get sunburn.”

When a “regular gully washer” wiped out their initial efforts, the would-be farmers replanted their potatoes, corn, and beans. Dent recalled, “We kept our plots well hoed and the vegetables in good trim until our June vacation, and having no Summer quarter to cause us to linger, we departed. . . . When we returned . . . a dreary waste of weeds ripening in the September sun hid from view the few surviving and decaying vegetables. As we looked upon our departed hopes we could not help but think that this is the seeming result of all man’s labor.”

Still, things worked out for Dent, who became WVU’s first (and only) graduate in 1870 and went on to serve as a judge on the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.