The Hatfields, the McCoys, and the Other Matewan Shootout

By F. Keith Davis

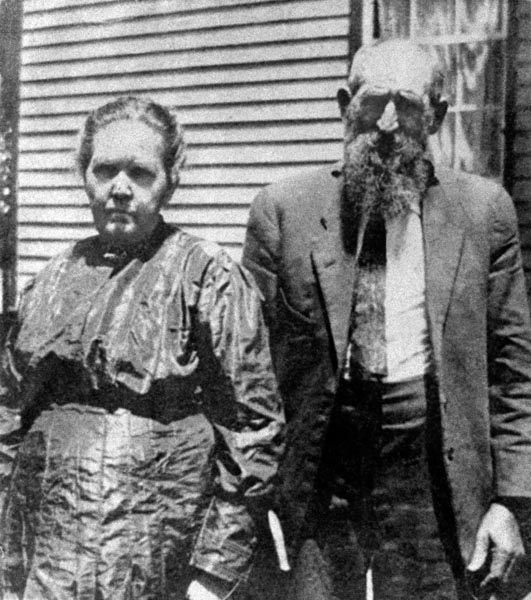

William Anderson "Devil Anse" and Levicy Hatfield are shown here later in life. Courtesy of the West Virginia State Archives.

“Cap,” as he was known back home, stepped down from a cramped passenger car. His worn, half-length leather boots clumped along on the rickety boardwalk of the small train depot. Tightly clutching his Model 1873 Winchester repeater, he peered through the belching clouds of steam. The lingering smell of burning oak—the locomotive’s fuel source—almost choked him as he gulped for air.

He peered around intently for anyone armed or suspicious. Gunnison City, Colorado, was smaller than he’d imagined—a cow town not much larger than where he was from in southern West Virginia. Much like home, mountains sheltered the community, but the barren stone formations stretched along the horizon, contrasting starkly with the lush Appalachian mountains of home. He was awestruck by the raw splendor as the sun rose over the foothills of the Rockies. As he assessed this strange environment, he was still convinced he’d made the right decision in running from the law.

Where he came from—perhaps the most rugged, isolated region of West Virginia—Cap was considered as proficient and dangerous with a pistol or lever action as any Old West gunslinger. So, how did this shootist from the Mountain State end up in the Colorado Rockies?

William Anderson “Cap” Hatfield was the second son of clan patriarch Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield. From the time he was a toddler, he’d been known as “Little Captain” after his father, who’d been captain of the Logan Wildcats, a loose band of Confederate irregulars active in Logan County and the surrounding area late in the Civil War. The nickname stuck, although it eventually was shortened to Captain, or, more frequently, just Cap.

Cap arguably had been the most violent accomplice in a nationally known blood feud between the Hatfields and McCoys in the late 1800s. The feud had raged off and on for years between the Hatfields of Logan County (now part of Mingo County) and the McCoys of Pike County, Kentucky.

Tensions between the two families likely went back decades but began escalating dramatically in 1878 after McCoy patriarch, Randolph, accused Floyd Hatfield of stealing a hog. From that point on, McCoy became obsessed with the Hatfields—to the point of rejecting his own daughter Rose Anna after she began seeing Devil Anse’s first son, Johnse.

The feud snowballed as one event triggered another. Shortly after the hog trial, in which Floyd Hatfield was found not guilty of stealing the pig, McCoy supporters killed Bill Staton, who’d testified on Floyd’s behalf. Then, on Election Day 1882, three of Randolph’s sons seriously wounded Devil Anse’s brother Ellison in a drunken brawl—apparently over a fiddle. Devil Anse gathered a posse and captured the three McCoy boys: Tolbert, Pharmer, and Randolph “Bud” Jr. When Ellison died, the Hatfield gang led their prisoners to the Kentucky side of the Tug Fork River, tied them to pawpaw bushes, and executed them firing-squad style.

During the ensuing years, several more murders occurred, but much of the drama unfolded in lawyers’ offices and in the state capitals of West Virginia and Kentucky. West Virginia Governor E. Willis Wilson continually refused to extradite the Hatfields to face murder charges in Kentucky. At times, it appeared the two states might go to war over the issue.

Perhaps the worst atrocity occurred on January 1, 1888. The Hatfields, led that night by Devil Anse’s uncle Jim Vance, hoped to end the conflict once and for all. They crossed into Pike County under the cover of darkness, set fire to the McCoy cabin, killed one of Randolph’s sons and a daughter, and bludgeoned his wife with a rifle butt. Randolph managed to escape the battle. A posse hunted down the perpetrators and “Bad Frank” Phillips, a former lawman and McCoy supporter, gunned down Vance within days of the New Year’s Day Massacre. In 1890, a Hatfield cousin, Ellison “Cotton Top” Mounts, was hanged for his role in the raid. This was the only legal execution of the entire feud.

According to many accounts, the feud died out after the hanging. This is largely because the two patriarchs, Devil Anse and Randolph, had grown weary of fighting. Both moved away from the Tug Fork—Devil Anse to Sarah Ann at Island Creek in Logan County and Randolph to Pikeville, Kentucky. Some family members and friends, though, weren’t as willing to give up the fight.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.