Dr. Emory L. Kemp: A West Virginia Preservation Pioneer

By Barb Howe

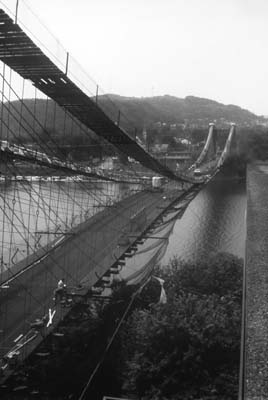

The Wheeling Suspension Bridge, which first opened in 1849, is one of the many restoration projects Emory Kemp has worked on in his more than 50 years in the Mountain State.

West Virginia University (WVU) historic preservation students lined up around the walls of an 18th-century room in Albert Gallatin’s home near New Geneva, Pennsylvania. It was a few years after the National Park Service acquired what would become known as Friendship Hill National Historic Site. The instructor rocked slightly on his heels, grinned, and asked, “Feel that?” as the floor vibrated underfoot. Yes, everyone, including this author, felt it. “There are structural problems here.” Welcome to a field trip led by Dr. Emory L. Kemp!

Emory is a national leader in industrial archaeology—which combines the study of history, engineering, archaeology, and architecture—providing a bridge between what novelist C. P. Snow called the “two cultures”: sciences and humanities. For more than six decades, Emory has embodied those two cultures, employing innovative methods while establishing organizations to protect the built environment.

His interest in the built environment started early, with his father, an architectural engineering graduate of the University of Illinois. As Emory recalls, history and structural engineering “have never been separated for me.” Attending the University of Illinois Laboratory High School during World War II, two teachers encouraged him to study history. “I was really pretty good at this,” Emory remembers, “even receiving a Daughters of the American Revolution history award. The war being on, I really got into it as only teenage boys can. Historical things were really important, but I went into civil engineering. That got me into structural work.”

After receiving the Ira O. Baker Award as the outstanding civil engineering graduate at the University of Illinois, Emory went to London on a Fulbright scholarship to study for a master of science degree at Imperial College London. In the 1950s, he started his career with Ove Arup, a global firm of consulting engineers, where he worked on the calculations for the roof of the Sydney Opera House in Australia, helping to transform Jørn Utzon’s sketch into an international landmark. Instead of overseeing the construction of the Opera House in Sydney, Emory earned his Ph.D. in theoretical and applied mechanics from the University of Illinois.

In 1962, WVU hired Emory as an associate professor of civil engineering. He chaired that department from 1964 to 1977 and then established the History of Science and Technology program in the Department of History. With the launch of WVU’s Public History Program in 1980, he taught courses on the history of technology and industrial archaeology.

Most students research a building’s history at a local library or archives. Emory’s students, however, learned to use surveying equipment, take large-format photographs, measure structures, and then translate that data into measured drawings. In 1991, he established the Institute for the History of Technology and Industrial Archaeology (IHTIA) and eventually brought in more than $13 million in funding. Although he retired from teaching in 1993, he continued to lead the IHTIA until 2002.

Wheeling: An Industrial Archaeologist’s Dream

Emory has had a long fascination with Wheeling. The city was an early transportation hub as people and goods moved west on the Ohio River, even before the National Road was completed to Wheeling in 1818. The Wheeling Suspension Bridge was the first bridge across the Ohio River, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was completed to Wheeling in 1852. There was so much commerce that the federal government opened offices in the new custom house in 1859. Wheeling was also a center for manufacturing glass, paper, textiles and clothing, and nails before the Civil War. The discussions leading to the creation of the new state took place here, and it was the first state capital. Later, Wheeling also would be known for its cigars and steel.

One of the city’s most exceptional structures—and most challenging from a preservation standpoint—is its suspension bridge, a National Historic Landmark that crosses the east channel of the Ohio River to Wheeling Island. Preservationist Beverly Fluty first piqued Emory’s interest in the span, which was the longest suspension bridge in the world when it opened in 1849.

“When I came in 1962,” says Emory, “I got associated with Beverly and got really intrigued by suspension bridges, back to the early Chinese. I was determined to do this on a historic basis, but suspension bridge analysis is pretty tricky.” In the process, he added to the work of Wheeling’s Father Clifford Lewis in proving that Charles Ellet, Jr., had designed the bridge.

Emory looks back on his work: “In the early 1980s, we put a covering on the bridge cables that was going to be waterproof, but we got leakage. The water ran down the cables, so you never knew where the water was coming from. The cables were packed in red lead when the bridge was built, and that preserved the wires. Red lead is wonderful stuff, but you’re not allowed to use it now. It’s toxic.”

“When the south cable came down during a storm in 1854, it had caused a big crack in the top of the stone tower on the Wheeling Island side. After really careful analysis, we drilled a hole from side to side through the tower and pulled the whole tower together with a tensioned bar.”

Emory and Beverly also worked together with the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation to restore the Wheeling Custom House. Emory gives Beverly tremendous credit for the building’s restoration: “I think she guided Tracy Stephens, the architect on the project, in all the aspects of what we did there. If it weren’t for Beverly, it wouldn’t have been done correctly. She was so meticulous.”

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.