Redeeming the Wood

Self-Taught Woodcarver Herman Hayes

By Colleen Anderson

Two stout figures lean toward each other, joined at the lips in an almost audible smack of a kiss. A miniature stadium holds a hundred wooden figures - each an individual personality - watching a wooden baseball game. In a piece that resembles an absurd acrobatic act, elongated bodies in fantastical contortions balance other bodies, some made of nothing more than a face atop a pair of legs. Whimsical, weird, and wickedly funny, the Reverend Herman Hayes' woodcarvings reveal much more than technical skill. It's impossible to look at them without sensing the artist's psychological insight and sheer joy in life.

Hayes has twice won the top award in the West Virginia Juried Exhibition and regularly sells his carvings for thousands of dollars. Nevertheless, when he travels, the retired preacher carries his artworks in a worn shopping bag held together with a length of twine. It's the sort of incongruity that delights him.

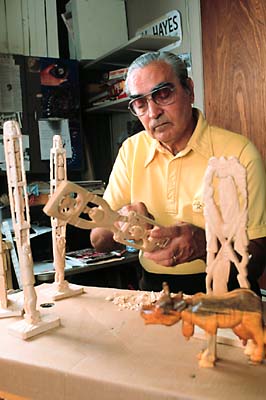

Rev. Herman Hayes has a unique gift for woodcarving. Photo by Michael Keller.

Herman Lee Hayes was born in Elkview, Kanawha County, September 23, 1923, to Nina Vesta Hayes and Owen Worth Hayes. Owen, who was driving a six-horse team in the local oil fields, met his future wife at her mother's boardinghouse, and they married in 1920. It was the second marriage for Hayes' mother, whose first marriage to a man named Milton produced one surviving child: Herman's half-sister Dorothy. His mother's maiden name, however, was the same as that of her second husband. "She was born a Hayes; I'm full-blooded Hayes," says her son.

The Hayes-Hayes union was blessed with seven more children - Delmar, Herman, Holley, Mary Arline, Flora, Jack, and Ralph.

Thanks to her boardinghouse upbringing, Hayes' mother was accustomed to setting a large dinner table. "They had 40 oil workers there at one time, feeding them. And my mom really knew how to cook," Herman recalls. His father soon began working as a pipe fitter for Union Carbide, a job that kept the family somewhat insulated from hard times during the Great Depression.

Even so, growing up in a big family during Depression times left strong impressions on young Herman. "Growing up in a family of eight, the one that got up the earliest was the best-dressed. We used to have a great, big, round table, and we'd kick each other under the table. I kicked my sister one time, and boy, that made her mad, and she had a fork and - wham! - four little beads of blood come right out. I didn't kick her no more."

Like most boys of his generation, he owned a pocket knife. His first whittling was strictly utilitarian. "You really couldn't call it whittling, but I used to make - out of sticks as big as your finger or maybe a little bigger - deadfalls. A deadfall is a great, big, flat rock. You jack it up, and you make a trigger that's notched here, and notched here, and they fit together. This one runs in back under the rock, and it has bait on the end of it. This top one here is holding your rock up. And a little animal gets back in there, chewing on that, and why - poof! That's it." The crude traps were not constructed for the sake of cruelty to animals. During the Depression, "a nickel was awful hard to come by, and I think we could get thirty cents for a muskrat hide."

Also during the 1930's, Hayes encountered his first real inspiration as a woodcarver. His father bought some handmade furniture. Along with the furniture, he brought home a wooden ball within a box, both carved from a single piece of wood. The puzzle fascinated Herman, and all-of-a-piece carvings continue to please him. Today a number of his carvings feature not only balls but collections of human figures within cages. Others have circular wheels of wood that actually turn, carved from the same block of wood that forms the frame within which the wheels spin.