Memories of a Mining Family

Tony Armstead Recalls Four Generations

By Sharon L. Gardner

Photographs by Mark Crabtree

In the fall of 1981, Tony Armstead became the fourth generation of his family to mine coal. Four years later, he had to walk away. "My choice would have been to stay with mining," Tony says. "I liked the work, and I wanted to follow in my dad's footsteps. But I decided against it."

From 1916 to 1987, there was at least one member of the Armstead family working in the mines. Tony's great-grandfather William Armstead was born in 1870. He entered the Alabama coalfields to escape sharecropping and worked alongside prisoners sentenced to mining as their punishment. Tony says, "My great-grandfather William brought his sons - my grandfather James and my uncle Clifford - into the mines as young boys. I can't imagine being nine years old and working underground, day in and day out. But they did it."

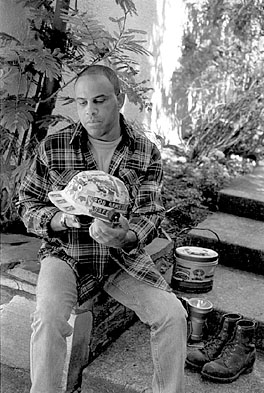

Tony Armstead sits outside his home in Morgantown and examines his father's mining helmet. Beside him are a pair of boots, a lantern, and a lunch bucket which also belonged to his father. Tony used the lunch bucket himself during his own four-year tenure in the mines. Photo by Mark Crabtree.

With the promise of better pay and improved working conditions, the three Armstead men and their families relocated to the northern West Virginia coalfields in 1925. After finding work in the Watson mine, they settled in the Marion County community of Watson, near Fairmont. Tony's father Bob was born there in 1927.

Grandfather James, whom Tony calls "Paw," moved his family to the racially segregated coal camp of Grays Flats, outside of Grant Town, in 1929. His job was driving horses hauling two-ton coal cars out of the mines. Although James worked hard, he struggled to support his growing family of 11 children during the Great Depression.

"From 1929 to 1941, they lived in a four-room, coal company house with no inside plumbing," Tony says. "Because Paw worked six days a week in the mine, my dad and his brothers had many chores to do. Also, the coal company charged way too much for coal to heat their home, so the boys gathered spill-coal from the trains."

The United Mine Workers local chapter elected James Armstead recording secretary and financial secretary in the early 1930's. "Paw was big on the union," Tony says. He wrote letters for miners who couldn't read or write. That's amazing for a man with a fourth-grade education who taught himself to read. He wanted the miners to get what they deserved for working so hard."

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.