Life In the Levi Shinn House

By Edwin Daryl Michael

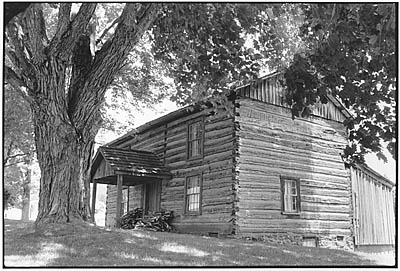

The Levi Shinn House, built in 1778, is the oldest standing structure in north central West Virginia. It stands along U.S. Route 19 in Shinnston. Photograph by Mark Crabtree.

Alongside U.S. Route 19 south of Shinnston is a two-story log house commonly known as the Shinn House. Built in 1778 by Levi Shinn, the house was the center of a flourishing frontier farm where Shinn and his eldest son, Clement, successfully raised two families, consisting of 17 children. This landmark is a remnant of a tumultuous time in the Appalachian wilderness, when more than 100 forts and blockhouses were built throughout the Monongahela Valley. During the 1944-1953 period, and for several years after, we knew the Shinn House as the Michael house. It was my family’s home.

In 1944, my father, Edward Michael, moved his family to the small Harrison County town of Shinnston, population 2,000, to open Shinnston Plumbing Company with two brothers-in-law. Born and raised in the Whetstone area near Mannington, Edward Michael’s vision of the ideal home was a country setting where he could have a garden, a milk cow, some chickens, and most importantly, his rabbit dogs. As a teenager, he had quit school and started working in Bowers Pottery Company at Mannington — at the time, the largest such pottery in the world. The pottery, with an annual capacity of more than 3,000 commodes and lavatories, brought jobs to hundreds of young men. However, along with the welcomed wages came something not so welcomed. After a few years at the pottery, Edward knew he had to change occupations, when a doctor warned him that his white lung illness, contracted as a result of thousands of hours of producing porcelain bathroom fixtures, was life-threatening. His wife, Isolene, had spent her childhood as one of eight children on the Harrison Gump farm a few miles from Farmington, up Plum Run. Edward and Isolene had wanted their two boys — myself and my brother Roger — to experience the joys and challenges of living in the country.

When we moved to Shinnston in 1944, I was six years old, five years older than my baby brother. My dad had found a house just outside Shinnston that met his requirements of good location, some land, and reasonable rent. However, on June 23, the house was totally destroyed by the infamous Shinnston tornado. [See “The Shinnston Tornado,” by Martha Lowther; Summer 1998.]

When the owner informed my dad that the house was gone, Edward immediately began searching for another house to rent. Unfortunately, the tornado, which killed 66 people and hundreds of farm animals, also destroyed more than 300 houses. Dad finally found a house about 10 miles from Shinnston, between Lumberport and Wallace, and paid one month’s rent as a down payment. Two weeks before moving, however, he learned of a big, old log house, which although very old, was in a much better location, had modern amenities, and was available for us to rent. Only fate decided which houses would be totaled and which would be spared by the horrible tornadic winds of the 1944 catastrophe. Although the 300-yard-wide path of the Shinnston tornado passed within a quarter mile of it, the log house built by Levi Shinn sustained damage only to the front porch, one outbuilding, and two trees. Throughout the home’s long history, the watchful eyes of its many occupants and considerable good fortune had somehow saved the log house from the destructive forces of Indian attacks, fires, insects, storms, and age.

Following a three-month delay for repairs, we moved into the Levi Shinn house in September. The original log house had two rooms downstairs and two upstairs. In the center of the house was a huge stone fireplace, with its main opening covering nearly one entire wall of the living room. The original occupants, and many who followed, depended on the fireplace, which was nearly 10 feet long and four feet high, for warmth and for cooking. The living room was truly the center of life in the original Shinn House. With its huge fireplace, cooking, eating, and most every other daily activity took place in that room. The other downstairs room, which contained only a small fireplace for heat, probably functioned primarily as a bedroom. Thus, on the coldest of nights, some of the occupants ended up sleeping on the floor in front of the huge living-room fireplace. While there was no direct source of heat in the two upstairs rooms, the exposed stone walls of the chimney would have radiated enough heat to make sleeping tolerable.

The original two-story log structure is much the same today as when it was first built in 1778, but it has undergone a few changes, some obvious and some not so obvious.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.