Asturian West Virginia

By Luis Argeo

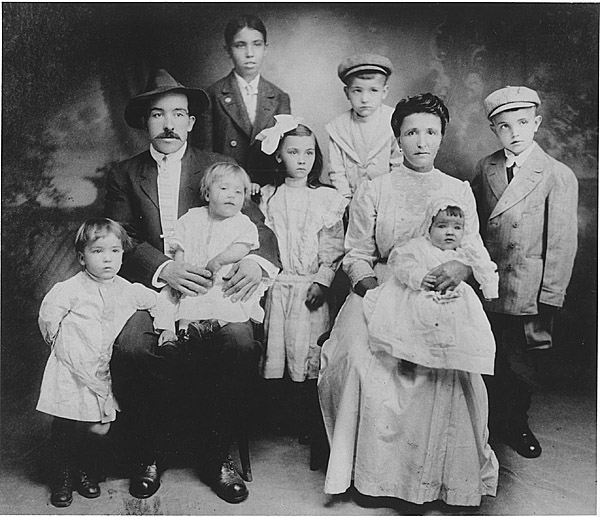

Spanish immigrants came to Harrison and Marion counties by the thousands

to work in the zinc factories during the early 20th century. The Diego

Vásquez family is pictured here in Spelter (Zeising) in 1912.

Photograph courtesy of West Virginia State Archives, Ruth Yeager Collection.

“We believed that they were going to the best place of the world, but they suffered a lot there. It was very hard for them. Very hard, yes.” Mrs. Covadonga Vega López speaks about her neighbors and relatives from Arnao, an Asturian coastal village that saw hundreds of metallurgical and mining workers shipping towards the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, far away, to the isolated mountains of West Virginia.

That was almost one century ago. They departed Spain seeking new opportunities, or as it is said in the movies, searching for the American Dream. The workers proceeding from the Arnao Royal Asturian Company of Mines ran up against a tepid welcome after landing at Ellis Island immigration offices in New York. They would eventually reach their own American Dream, although splashed with indifference, difficulties, and discrimination.

Their labor experience in mines, factories, and blast furnaces in their home country led them to those places where chimneys, shafts, and cooling towers proliferated among the woody green and the stony black of the coal valleys. They gathered in small company towns that were built for workers close to the factories — towns that belonged to the chemical and mining companies, with low-rent houses, storehouses, school, and church: towns like Spelter, Anmoore, and Moundsville in West Virginia, and Donora in Pennsylvania.

These were towns where Asturian immigrants were in the majority, places where for many years people could speak the Asturian language, ate fabada (mixture of beans and rice with chicken), played the bagpipe, and danced the traditional Xiringüelu for fun. Asturian and United States histories converged in the hills, valleys, and rivers of the Appalachian region, thanks to the zinc workers.

“Wherever there were zinc factories, there were Asturians. They were those who better could stand such a nasty and helly work,” Isaac Suárez, octogenarian, son of Asturians, and born in Spelter, says in Spanish. “That’s why the Spanish language was very common in the smelting furnaces.”

“The Asturians involved in the zinc industry thought of themselves as one community,” says Art Zoller Wagner, grandson of another Asturian who arrived in West Virginia in 1917. “They communicated with each other; traveled to each others’ fiestas, weddings, and funerals; and shared news about job opportunities. The experience of any of the locations would have had much in common with the others.”

Spelter, Harrison County, is today a dismantled and silent residential Clarksburg suburb. Nevertheless, its 175 wooden houses hosted 1,500 people of Asturian origin in 1915. All the families depended on the zinc mill that Grasselli Chemical Company had raised at the edge of the West Fork River. All of the families knew each other and, by and large, they were a happy community.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.