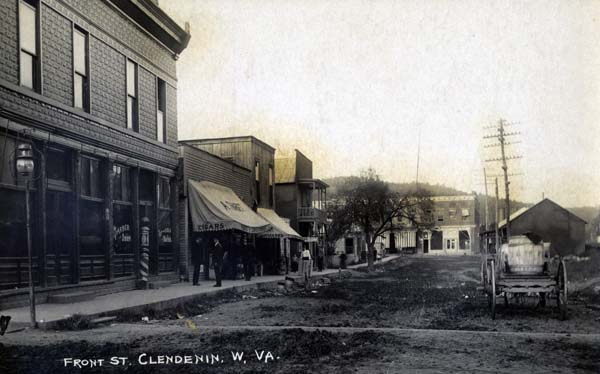

Clendenin

This is one of the earliest photos of modern Clendenin, perhaps about 1905. Among the businesses in this block are a barber shop

that advertises "hot & cold baths" and Thabet's grocery and restaurant.

Nobody in Clendenin had ever seen Elk River run so high. Between the afternoon of Thursday, June 23, and the morning of Friday, June 24, the river rose 27 feet before cresting at 33 feet. The town was accessible only by helicopter. Some heard stories that it was on par with the flood of March 14, 1918. A few older residents can still recall the high-water marks from 1932 and 1937. But the 2016 flood is the highest ever documented at Clendenin—going back 125 years of record keeping—including the New Year’s Day 1888 flood, which crested at 32 feet.

Like most places in West Virginia, it was the river that attracted early prehistoric cultures and later white pioneers. Most early settlers in this area built their homes on fertile bottomland near the mouth of Big Sandy Creek, across the Elk from the present-day downtown. The names of pioneering families are still commonplace in Clendenin: Cobb, Price, Jarrett, Young, Stricklin, Shamblin, Hays, Woods, and Davis, among others.

While it was primarily a farming region, it also was the site of one of Western Virginia’s first coal booms. Cannel coal is highly volatile and burns easily. In the 1840s, makers of home lanterns began replacing whale oil on a wide scale as a fuel for lanterns (hence the name “candle,” or cannel, coal). Some of the wealthiest families in New York and Philadelphia were regular customers of cannel coal oil from Kanawha and Boone counties. A large distillation plant was built at Falling Rock, just south of Clendenin. A natural gas refinery, known as Elk Refinery, was later operated on the site from 1915 to 1983.

A few years later, the fortunes of cannel coal took a tumble with the advent of kerosene, a much safer home lighting source. By the end of the Civil War, cannel coal no longer had the same value. Most mines closed, as did the distillation plant.

Clendenin remained mostly a sleepy farming region until June 1893, when the Charleston, Clendenin, and Sutton Railroad arrived. It initially connected Clendenin with Charleston and opened the region to timbering. Seven years later, the first gas well was drilled in the region, and Clendenin became the heart of an oil and gas boom in northern Kanawha and southern Roane counties. The Cobb Station Compressor Plant, completed in 1920, was once considered the largest in the world.

A spinoff of the oil and gas industries started at Clendenin in 1920 when Union Carbide built the world’s first petrochemical plant—producing synthetic chemicals from natural gas. Trailblazing chemist and early Carbide official George Curme commented years later on what the company produced during those first years at Clendenin: “Mostly, a lot of mistakes.”

Carbide soon relocated to South Charleston, and the Kanawha Valley became the nation’s chemical capital. But the oil and gas boom had already put Clendenin on the map, with a thriving downtown section.

Much of the Clendenin Historic District dates from the 1890s to 1920s. While the buildings were built sturdily—most have withstood the test of time—the roads in and around Clendenin were another matter due largely to oil and gas teamsters lugging around pipes and loaded barrels. In 1911, historian W. S. Laidley made this observation about the town’s thoroughfares: “We may be pardoned for speaking of the ways as roads, for of all ways that either teams or horses or people had to pass over, some of these are the worst, and few, if any, could be worse than the streets.” Laidley added wryly, “There is plenty of good Elk River water to drink, gas to burn, but they have voted out the saloon and have no use for policemen.”

By the mid-20th century, the oil and gas industries were on the wane, but Clendenin persevered. After Interstate 79 was completed in the 1970s, much of the area around Clendenin and nearby Elkview began to transform into a bedroom community for Charleston. While business might not have been what it was in the early 1900s, there was still a thriving downtown, until the floods of June 23-24. Every building in the business district was damaged—some more than others. But Clendenin has survived before, and it will survive this latest blow.

“If we don't watch out for others in the community,” said Clendenin resident Craig White, “who's going to?”

His sentiments could be the motto of every small town in West Virginia.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.