The Lady is a Fireman

Amy McGrew of Cass

Text and photographs by Carl E. Feather

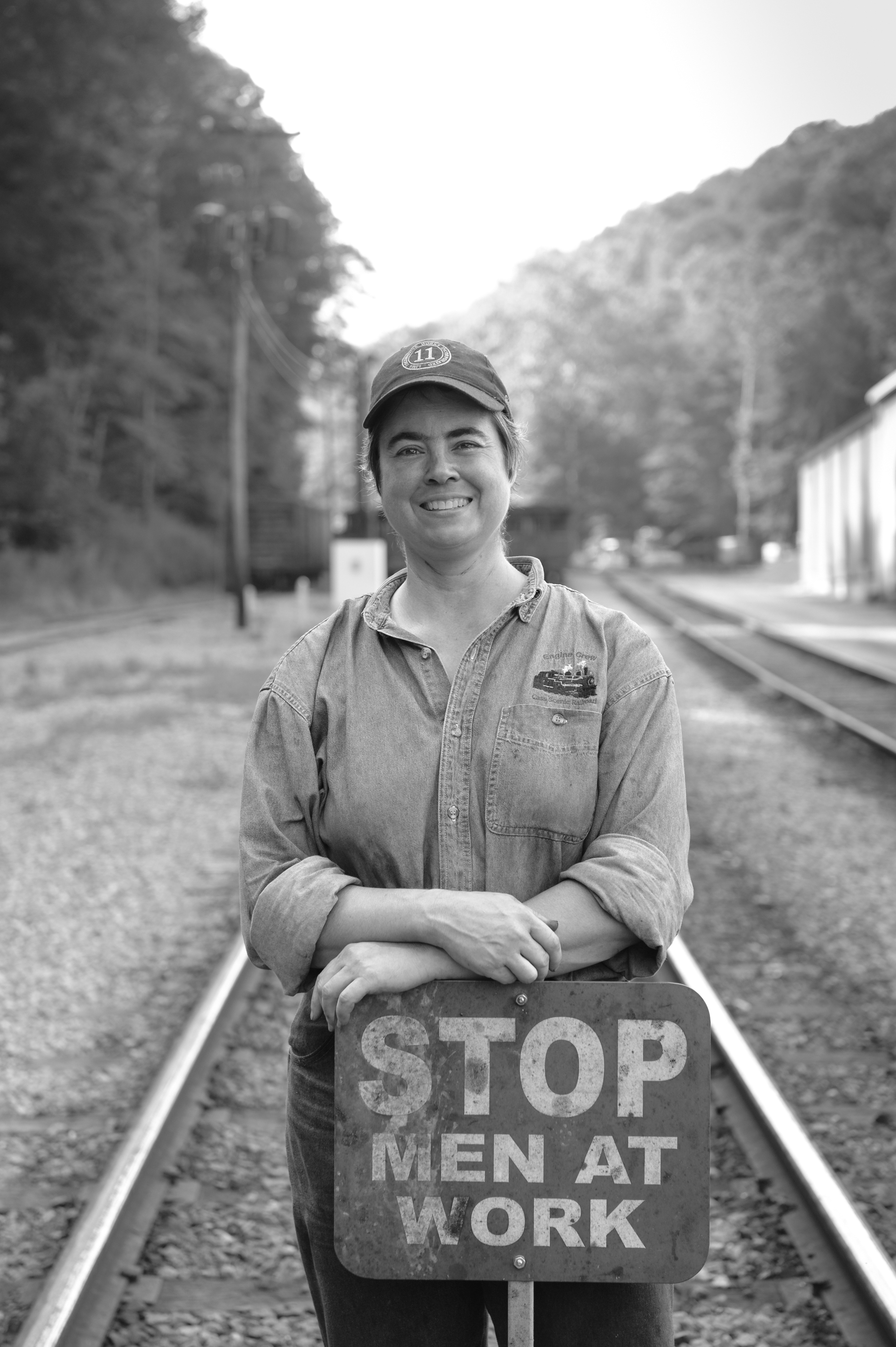

Amy McGrew, first female fireman for the Cass Scenic Railroad. Photograph by Carl E. Feather.

Amy McGrew recalls the day she unwittingly attended a cosmetics party at a friend’s house, where the demonstrator asked each lady to share the name of their favorite beauty bar.

“Lava,” Amy said.

“No, I mean for your face,” the demonstrator replied.

“Lava,” Amy said.

Amy’s job as a fireman on the Cass Scenic Railroad in Pocahontas County requires she exchange many of the traditional female niceties for the coarser mainstays of the male world. Her uniform includes steel-toed boots, insulated gauntlets, jeans, a blue-denim Cass SRR shirt, and ball cap. A few minutes after starting the shift, her crisp shirt is dappled with perspiration, cinders dust the back of her jeans, and soot from the engine encircles her neck. It only gets worse as the workday goes on.

“I find that, physically, getting the engine ready is more demanding than firing,” Amy says, taking a break from preening the locomotive and tender for the day’s first run. “But once we get going, I’m sweating more than I’m working."

Hundreds of times during the 11-mile run to Bald Knob, she opens the locomotive’s firebox, a 5x5x7-foot inferno on wheels, and artfully feeds the ravenous behemoth, ever mindful it could belch without warning and singe her eyebrows in the process. The temperature in the cab typically runs 20 degrees hotter than the ambient air; to counteract the loss of water through sweat, Amy drinks a couple of gallons of ice water during a typical firing shift.

Amy jokes that there are so many dangers on her job, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) wouldn’t know where to start regulating it. Despite the dangers, Amy considers herself extremely blessed to be doing the work of a fireman on West Virginia’s original scenic railroad, a job that many men wash out of and that women rarely get the opportunity to attempt, let alone succeed at for five years.

“It is a combination of the physical work and repetition,” Amy says of the factors that force many wannabe firemen to drop out. “It is a very repetitive job.”

Amy takes great pride in her perseverance and performance. “There has never been a female fireman [on the Cass Scenic Railroad], that anyone here is aware of,” Amy says as she takes a break at Bald Knob on a hot, humid Sunday in late July. She notes, however, that during World War II, when many logging railroad engineers and firemen were called to military duty, their wives stepped up to the engine in order to meet the family’s financial needs and maintain the flow of timber to the mills. But, on the company’s records, the husbands were still running the locomotives.

Firing the locomotive is arguably the most physically demanding and potentially dangerous job on a steam locomotive. Amy says most people would flunk the screening application, if there were one.

“There are so many things you can’t be afraid of doing this job,” she says. “You can’t be afraid of heights, you can’t be claustrophobic, you can’t be afraid of getting burned, hurt, or squished. And you have to like loud noises.”

Watching Amy at work, there’s no doubt that she suffers none of those phobias. Her pre-run routine includes a thorough cleaning of the locomotive and tender, which involves climbing the boiler jacket and wiping it down with a cloth. As she works, she gingerly avoids the myriad pipes carrying 200 pounds of steam pressure that could leave a nasty burn on her arms or face with one misstep.

“I usually get burned every couple of months, but sometimes it is every other week,” Amy says matter-of-factly, her forearm bearing the marks of a recent encounter with the locomotive’s heat.

Her cleaning work also takes her near the relief valves, which can pop open at any time with a deafening hiss and blast of the super-heated steam that makes most observers jump. Amy admits she hates the noise, but at the same time she’s in tune with it.

“I just know from the sound of them if they are going to open, and I’m aware of what direction the steam will go in,” Amy explains.

She says that while the job is fraught with dangerous situations, being aware of her environment and having respect for the equipment go a long way toward keeping her safe, both on the train and in the shop, where she works during the winter months.

In the shop, the work can be just as strenuous and dirty as shoveling the several tons of coal that the locomotive will burn on a trip to Bald Knob. Amy says the dozen or so full-time employees who tear down and rebuild the engines and cars are a special breed of workers. They take great pride in their occupation, but also are very opinionated about how the work ought to be done.

"You are not going to get docile, passive people to do this kind of work," she says.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.