"You write songs like people breathe":

Billy Edd Wheeler, Renaissance Man

By Michael M. Meador

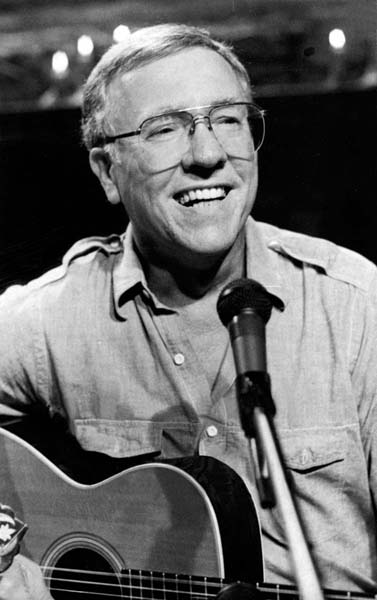

Billy Edd Wheeler, 1989. Photographer unknown.

For more than 50 years, Boone County native Billy Edd Wheeler’s music has inspired us, brought tears to our eyes, and made us laugh. His songs have been covered by artists as varied as Elvis Presley, Jefferson Airplane, Gram Parsons, Neil Young, Bobby Darin, and Richie Havens, who opened his set at Woodstock with Billy Edd’s “High Flyin’ Bird.”

The first line of Billy Edd’s “Jackson” is one of the most memorable in country music: “We got married in a fever, hotter than a pepper sprout.” This megahit won a Grammy for Johnny and June Carter Cash and was later ranked by Country Music Television as one of the 10 greatest love songs in country music history. In 1980, Kenny Rogers had a blockbuster hit with “Coward of the County,” which Billy Edd cowrote with Roger Bowling.

Billy Edd, who’s never won a Grammy himself, has received virtually every other honor in the music world. He’s a member of the Nashville Songwriters Association International’s Hall of Fame and the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame. He was also in the inaugural class of the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame, in 2007.

Billy Edd was born in 1932 in Whitesville and didn’t know his biological father’s name until he was 11 years old, and finally met him briefly when he was 17. He was raised by his mother’s parents in Jarrolds Valley, about a mile as the crow flies from Whitesville. After his mother got married, she took Billy Edd to live with her and his stepfather, Arthur Stewart, who worked in the Anchor Coal Company’s lamp house at Highcoal, about six miles from Whitesville. The town of Highcoal was run by Superintendent Van B. Stith, who Billy Edd remembers as “lord and king of the coal camp.”

As in most coal towns, the houses of superintendents, foremen, and doctors were nicer than those of the miners. “We didn’t have running water or indoor plumbing,” says Billy Edd. “We had to carry water from a pump. We were at the head of the holler, so the creek was pure enough for us to wash clothes with it. My mother would put out a washing by boiling clothes in a big tub. I would stretch a piece of feed sack across that tub and hold it in place with clothespins. Sometimes, there would be a minnow flopping around!”

Highcoal was one of the many once-thriving West Virginia coal camps that have now reverted to ghost towns. But Billy Edd can recall the town’s heyday, “The poolroom there was the center of activity. It was a very plain building, just cinder blocks, where you could get a haircut if you wanted to. And then you went on into the large room where on the right you could buy beer. On the left, you could buy candy and ice cream and soft drinks. In the back, that’s where the men played pool. Upstairs, they used to have boxing matches, and I saw my first movie there, a black-and-white film about Frankenstein.”

Billy Edd has mixed memories of those early years. He and his stepfather didn’t get along very well. But he also remembers loving relatives with whom he stayed from time to time, such as his Aunt Jean at Peach Creek and Aunt Louise at Red Dragon, just a few miles from Whitesville Junior High. Another was his Uncle Vincent. Billy Edd used to ride, rain or shine, in Vincent’s coupe, which had an uncovered rumble seat.

“One of my thrills in life,” Billy Edd remembers, “was to sit on Uncle Vincent’s lap and steer the car when I was five and six. He’d have his hands at the ready, but can you imagine how exciting that was? And you know those West Virginia roads were curvy, so that was a gigantic thrill for me.”

At Highcoal, Billy Edd went to a one-room grade school with a pot-bellied stove in the middle of the room. His first- and second-grade teacher was Sylvia Carter, who had a big influence on his life. Her husband, Clyde, was the number two man at Highcoal. Billy Edd moved on to Whitesville Junior High and then Sherman High at Seth. He remembers West Virginia Route 3 from Whitesville to Seth being like an “interstate” compared to the road up to Highcoal.

It was about this time when he started signing his middle name with an extra “d” because, as he noted later, he “liked the way it looked.” At one point, Billy Edd took on a newspaper-delivery job, which inspired his first song, “Paperboy Blues”:

I’m just a paperboy, rise up so early in the morning

I’ve got that lonesome feeling

Feeling comes on me without no warning

They say, Good morning, Mr. Paperboy

Man, it ain’t no good mornin’ for me

Good mornin’, Mr. Paperboy

Man, it ain’t no good mornin’ for me

‘Cause I hear that wind a blowing through them hickory trees

Billy Edd reflects on his first songwriting attempt: “It’s not memorable, but I created it, and I was proud of it at the time.”

Billy Edd’s family didn’t listen to music often. His first musical experiences occurred at an interdenominational church in Highcoal. Billy Edd says, “There was a black man . . . who came to teach us shape-note singing: ‘Do, re, me. . . .’ The shape of the note had something to do with where it was on the musical scale. One was a block, one was a half-moon, etc. That’s why they called them shaped notes.

“And then one of my buddies, Paul Morton, had a small record player, and he played this gospel song, ‘Talk About Jesus.’ I remember, we played it over. It was well produced, and the harmony was great. That was one of the first commercial recordings that I heard.

“There was another guy who showed me some chords on the guitar; he was a coal miner named Gene Green. He could yodel like Eddie Arnold.

“I think I was about 12 when I got my first guitar: a Sears and Roebuck $14 guitar. It was an arched-top Kay, and the strings were so high off the fretboard your fingers would practically bleed from pressing down so hard. You had to really want to play on that guitar to stick with it. But after a while, your fingers would get calloused, and it didn’t hurt anymore.”

When Billy Edd was 12, he ran away from home, walking alone without a flashlight through an unlit mile-long railroad tunnel to reach Kayford in Kanawha County. He hitch-hiked to his grandfather’s house, about eight miles away at Eskdale. His mother and stepdad came to get him, but Billy Edd ran away again the next morning—this time, with a flashlight. When he got halfway through the tunnel, a coal train came roaring through and scared the wits out of him.

Billy Edd stayed about a year with his widowed grandfather, who looked the other way as his grandson regularly skipped school at East Bank High. As Billy Edd recalls, though, his granddad wasn’t so forgiving on one occasion.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.