Echoes of Buffalo Creek: An Introduction

By John Lilly

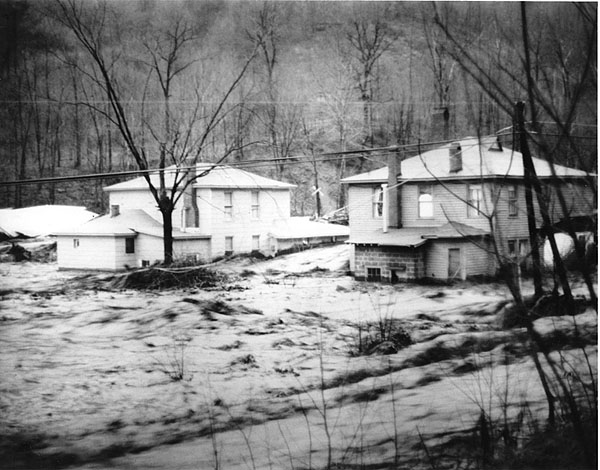

Water, coal sludge, and debris rage through Buffalo Creek Valley, Logan

County, on February 26, 1972. Photographer unknown, courtesy of Glen Jackson

They still have nightmares whenever it rains. The survivors of West Virginia’s most deadly flood disaster carry the indelible scars of a tragedy that didn’t need to be. On the morning of February 26, 1972, 15 miles of the narrow Buffalo Creek Valley in Logan County were scoured by more than 6 million cubic feet of coal waste, water, and debris. In its wake, 125 were left dead. Seven were never found, and three were never identified.

The Buffalo Creek flood actually had its roots in a minor tributary, the Middle Fork of Buffalo Creek, located 12 linear miles northeast of Man, where Buffalo Creek empties into the Guyandotte River. Coal mining began in this area around 1900 and increased when the C&O ran rails up the valley in 1914. In time, approximately 17 small communities developed along Buffalo Creek, many of them at the mouths of small streams, others at wide spots in the valley.

The town of Saunders was located at the mouth of Middle Fork. Most of the men there worked for the Lorado Mining Company, which began operations in 1945, opening a preparation plant, or tipple, two years later. Refuse from the prep plant was trucked to the foot of the holler and dumped in an ever-growing waste bank, or gob pile. In 1959, they began to pump waste water, which had previously been vented directly into the stream, into a reservoir formed behind the coal waste. The idea was that the water would be filtered by the coal waste and could then be recycled. The effectiveness of the reservoir improved in 1960, when Lorado began surface mining, which produced finer particles of waste, resulting in a large water impoundment.

In 1964, Lorado Mining was acquired by the Buffalo Mining Company, which continued to dump coal waste and impound water, pumping between 400,000 and 500,000 gallons a day, including about 500 tons of suspended solid waste, into the settling pond.

In 1967, a minor breach of the waste bank caused an explosion as liquid waste interacted with the smoldering gob pile, doing local damage at Saunders. The company responded by building a second waste bank, called Dam 2, just above the original impoundment, now called Dam 1. These impromptu structures were hardly dams in any technical sense, however. They were simply piles of coal waste, clay, shale, red dog, and other by-products of the coal preparation process, dumped off the back of trucks and bulldozed to an even height. Many in the downstream communities were keenly aware of the unstable nature of these impoundments, and expressed their concern to government officials.

You can read the rest of this article in this issue of Goldenseal, available in bookstores, libraries or direct from Goldenseal.