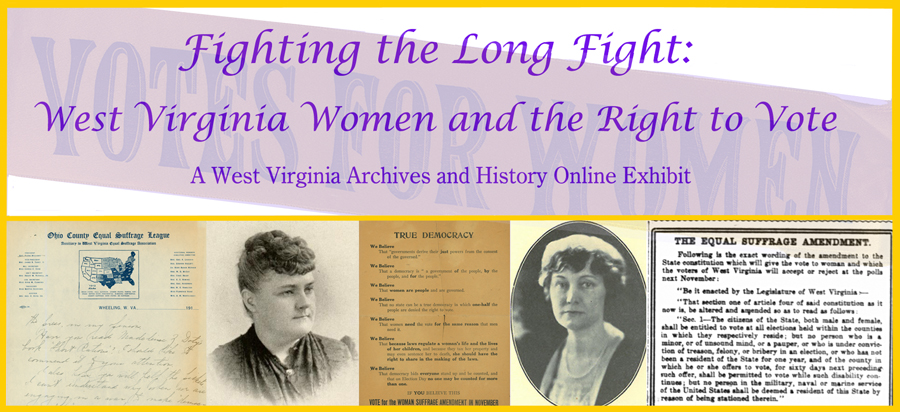

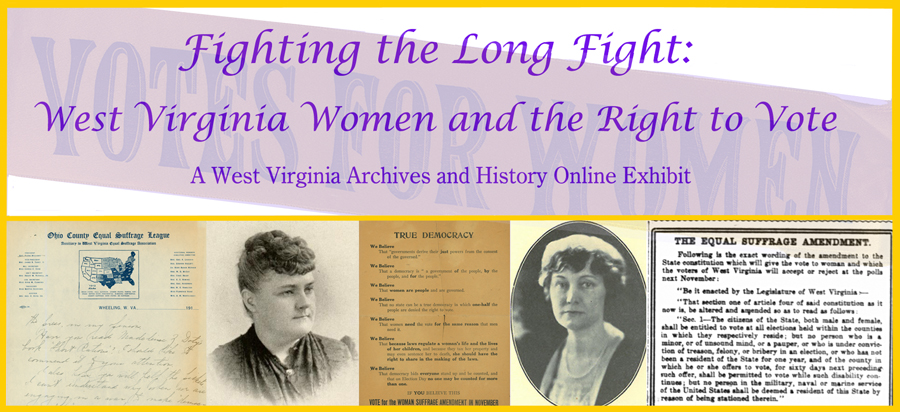

Chapter One

Beginning the Long Fight

In 1867 and again in 1869, West Virginia State Senator Samuel Young of Pocahontas County introduced resolutions supporting suffrage for women. In his 1869 resolution, Young proposed

“That we respectfully recommend that while the Constitution of the United States is being amended, extending the right of suffrage to all men over twenty-one years of age [giving African American men the right to vote], that the same right be granted, at least, to all women over twenty-one years of age, who can read the ‘Declaration of Independence’ intelligibly, write a legible hand and have actually paid tax the year previous to their proposing to vote.”

The resolution was defeated by a vote of 8 to 12 on February 9.

Williams letter to Fleming, April 2, 1892

Aretas Brooks Fleming Papers

|

Suffrage for women apparently did not receive further attention in West Virginia until the 1890s, when the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) briefly gave more attention to state organizing. In 1892, Mary H. Williams of the Committee on Governors’ Opinions of the NAWSA wrote letters to 49 governors of states and territories seeking their opinion on woman suffrage and providing a series of questions for the governors to answer. Fewer than one-half replied, but among the respondents was Governor A. B. Fleming of West Virginia. Without elaborating further, Fleming answered “No” to every question. |

"Are you willing that women should vote on exactly the same terms as men?

Are you willing to vote for an amendment to the Constitution giving to all citizens the right to vote in 1896, both male and female, who can read and write the English language?

Are you willing that women shall vote, provided there is for them an educational qualification?

Are you willing that women shall vote in municipal elections?

Are you willing that women shall vote in all school matters?

Are you willing that women shall vote under any conditions?" - Proceedings of the 25th Annual Convention, NAWSA, 1893 |

Three years later, in January 1895, Harvey Harmer, a freshman delegate from Harrison County, offered a joint resolution that would have amended the West Virginia Constitution to give women the right to vote. Upon request, U.G. Young, freshman senator from Upshur and an opponent of woman suffrage, introduced it in the Senate. The House of Delegates took no action, while the Senate defeated the resolution by a vote of 2 to 22, two senators absent.

By 1895, West Virginia was one of only two states in which no woman suffrage organization existed. However, in November, the NAWSA called a two-day meeting in Grafton to create one in the state. The West Virginia Woman Suffrage Association was formed, and Mrs. Jessie Manley of Fairmont was elected president. Other officers were Mrs. Annie C. Boyd of Wheeling, Mrs. L. M. Fay of New Cumberland, and Mrs. K. H. DeWoody of Grafton. Local clubs were organized in Benwood, Clarksburg, Fairmont, Grafton, Mannington, New Cumberland, New Martinsville, Wellsburg, and Wheeling. Only two of the local clubs—Fairmont and Wheeling—still existed a year later, and it was these two clubs that continued the work for the next several years.

|

"the constitution of West Virginia, if it prohibits you from granting to the ladies of Wheeling the right of suffrage, is unconstitutional." - Mrs. G. E. Boyd, Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, August 4, 1896 |

Three Wheeling women—Annie Caldwell Boyd, Dr. Harriet Jones, and Fannie Wheat—approached a committee working on a new municipal charter in August 1896 to request that women be granted the right to vote in city elections. Mrs. Boyd gave a forceful speech to the group of men, and Dr. Jones and Mrs. Wheat also pleaded their cause. Wheeling women did not obtain the right to vote. Nor did West Virginia women succeed in having woman suffrage inserted in the state constitution when a legislative committee considered amendments in the Spring of 1897. A proposed amendment was submitted to the constitutional committee, which apparently did not permit its supporters to express their views and indefinitely postponed it, effectively killing it, on May 26. Two years later, Fannie Wheat, president of the state suffrage association, asserted, "School Boards turn a deaf ear, City Councils are oblivious, while legislators openly scoff at our claims." (Proceedings, 1899) |

"West Virginia women are conservative, being southern women: hence the movement is not so strong here as elsewhere, . . .

West Virginia will be slow to move, . . . but from the little experience I had at the last session of the legislature, where I was using my efforts for the passage of a bill, I think that the right of women to vote will find favor with many. It is to men that we must appeal, . . . . I would like to see our cause publicly attacked, because then we could enlist additional aid, for in the discussion that would follow I am sure the opposition would have little ground to stand on." - Dr. Harriet Jones, Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, March 29, 1897 |

By 1900, women in four states—Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Idaho—had the right to vote, and they also could vote in the territories of Washington and Montana. In some places, women had a partial right to vote, in municipal elections or, more typically, elections concerning school matters.

Wheeling Intelligencer, December 13, 1900

West Virginia suffragists continued the fight into the new century. The fifth annual convention of the West Virginia Woman Suffrage Association, meeting in Fairmont in December 1900, decided to pursue legislation giving women the right to vote for presidential electors. Bills were introduced in 1901 in the House and Senate by Sen. Nelson E. Whitaker and Hon. Henry C. Hervey. Defeated on a vote in the House, the measure was effectively killed in the Senate when the enacting clause was removed. The association's president, Beulah Boyd Ritchie of Fairmont, blamed the Senate defeat on U.S. Senator Stephen B. Elkins, who was in Charleston at the time.

M. Anna Hall, 1903. Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Kansas, 1903

|

In 1904, the West Virginia Woman Suffrage Association changed its name to the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association at its convention in Moundsville, which, together with Benwood, had organized new suffrage groups. In addition to electing Mrs. M. Anna Hall of Wheeling as president, the convention approved several resolutions including these two:

|

"2. Whereas the home is the foundation of human society and whatever tends to broaden women's minds and deepen their sense of responsibility tends directly to promote the happiness and stability of the family relation; therefore

Resolved, That equal suffrage should be granted to the mothers of the republic not only for the sake of the state, but also for the sake of the home. . . .

6. That the women of America are not less intelligent, virtuous and patriotic than those of other countries where women are voting with benefit to themselves and the state and we call upon the men of our state, the most chivalrous men in the world, to show equal confidence in their mothers, daughters, sisters and wives by entrusting them with the ballot." - Wheeling Register, August 11, 1904 |

|

| Later that year, Wheeling women again approached a committee that was drafting a new city charter to seek woman suffrage. This time, however, the men agreed to let Wheeling voters decide the matter. The Woman's Political Equality Club and Woman's Municipal League worked together on the campaign under the leadership of Kate Gordon of New Orleans. The women created a campaign organization that had a central committee, comprised of Mrs. Edward Hazlett, Dr. Mary Baron Monroe, Mrs. E. M. Flood, Dr. Harriet B. Jones, and Amanda List, and ward chairmen for the city's eight wards, including Mrs. Hazlett, Dr. Jones, Dr. Monroe, Mrs. Flood, Anne Cummins and M. Anna Hall. The Reverend Dr. Anna Shaw, president of the NAWSA, spoke in Wheeling on several occasions during the campaign. To the surprise of the suffragists, they lost in the January 1905 election, garnering only 37 percent of the vote. Only the city's Seventh Ward, Wheeling Island, supported the proposition. "Thoug[h] we were defeated Thursday we are not dead, but intend to fight till we secure the right of suffage," Dr. Harriet Jones stated. (Intelligencer, January 28, 1905) While the campaigning for woman suffrage was underway in Wheeling, several Benwood women tried unsuccessfully to have a woman suffrage clause included in that city's charter. A month later, Fairmont women petitioned the West Virginia Legislature without success to amend Fairmont's charter to allow women to vote. |

Harriet Jones, 1890s. American Women: Fifteen Hundred Biographies, 1897

|

Anna Howard Shaw. The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony by Ida Husted Harper, 1898

|

Primary Documents:

West Virginia Woman Suffrage Convention Call, 1895

Formation of Fairmont Suffrage Group, 1895

Formation of Wheeling Suffrage Group, 1895

“We Want to Vote,” 1896

Alternative Proposition, Providing for Female Suffrage, 1905

"Women Reply to Germans Appeal," 1905

"Complete Vote of City Election," 1905

Previous Chapter |

Next Chapter

|