Fort Seybert Massacre

Grant County PressMay 13, 1937

New Interpretations Of Fort Seybert

(By Mrs. Lee Keister Talbot)

New Interpretations Of Fort Seybert

(By Mrs. Lee Keister Talbot)

April 27 and 28 of this year marked one hundred and seventy-nine years since the disasters at Fort Upper Tract on the South Branch of the Potomac, and Fort Seybert on the South Fork of the South Branch. So far little is known of Fort Upper Tract except that it was burned, a number of people killed and captured with few names left behind. A little more is known of Fort Seybert "the history of which, says DeHass, "fills such a dark page in the annals of Virginia."

Fort Upper Tract was built "at Hugh Man's Mill in Shelton's Great Tract," (familiarly known as Upper Tract of Virginia) in 1756; it appears that today it[s] location is not known.

Fort Seybert, also, was built within one hundred yards of a mill which had been erected at the edge of the river some years before Fort Seybert was built. The first owner of the land was John Patton, Junior, who purchased from Robert Green of Orange on the 5th of November, 1747, 210 acres of land "on the southernmost fork of the South Branch of the Potomack." This land had a "corner to Roger Dyer." In the Original Petitions filed in Augusta County for 1751-52 there is a petition for a road "from Widow Cobern's Mill, on the South Branch, to John Patton's Mill on the South Fork."

On May 21, 1755, John Pat[t]on, Jr., sold his land to Jacob Seybert. It is assumed that Jacob Seybert used the mill, and that the location of the Fort on his land may have been determined by its proximity to the mill. As recently as the last fifty or sixty years, people, when plowing in the field by the river at Fort Seybert have found "tight rocks." The tradition is that they marked the site of an old mill.

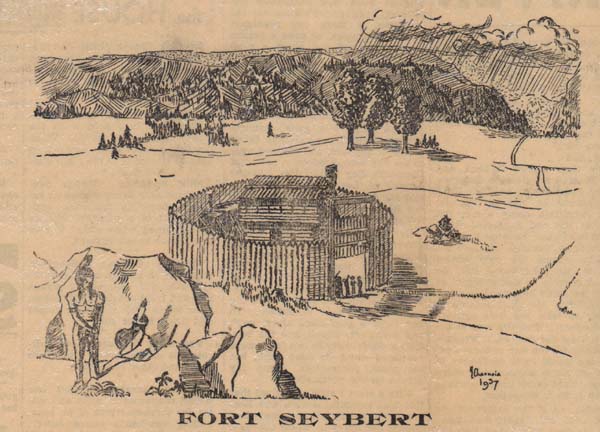

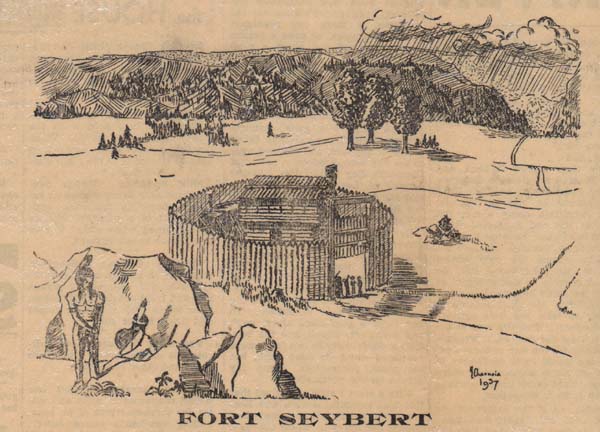

Plans for the building of Fort Seybert have not yet been uncovered in records, but there has been for some years a discrepancy between the pictured representation of Fort Seybert given by DeHass, and the remaining depressions in the ground at the site of the fort, as well as in the description handed down by those living in the vicinity of Fort Seybert.

The DeHass picture is a wood engraving with no artist's name attached. An authority on wood engravings finds it difficult to trace the origin of this type of drawing, as they were frequently made by the printing company, when printing a book, after the manner that lithographs are made today. This represents Fort Seybert as a large, square stockade, much after the fashion of the conventional combined trading-post and fort, sufficiently extensive to provide for a large garrison. This picture has been used repeatedly by historians as a source of description, and is the source of Mr. Koontz's information as to its size and strength.

DeHass says: "It was a rude enclosure, cut out of the heart of the forest, but sufficiently strong to have resisted any attack from the enemy had the inmates themselves been strong." People living in the vicinity of Fort Seybert today state that they can still trace the depression in the ground where the palisades were sat on end, and can well remember when the depression was more distinct than it is now. They consider it impossible that it was a number of log houses so built as to form a square or rectangle.

Mr. Alonzo D. Lough, who lives at Fort Seybert, wrote a description of Fort Seybert some years ago as follows:

"Fort Seybert was located on the left hand side (west) of the South Fork River, and situated on an elevation which sloped rapidly to a ravine on the north and descended abruptly over a ledge of rocks to the river on the southeast. Westwardly a gradual incline sloped back to the mountain.

"The defense consisted of a circular stockade some thirty yards in diameter, consisting of logs or puncheons set on end in the ground, side by side, and rising to a height often of twelve feet. A puncheon door closed the entrance. Within the stockade stood the two storied block-house twenty-one feet square. From the upper loop-holes the open space about the fort could be swept by the rifles of the defenders."

The drawing pictured above does not represent this description of Fort Seybert as accurately as might be desired, and a more accurate drawing will be made. However, this more nearly answers the description given by those living in the vicinity, and handed down traditionally for generations.

There were numerous causes of the Fort Seybert massacre, both remote and immediate; some of them have gone unnoted. Reverberations and echoes of it continued for many years. There are notations in Augusta county records as late as 1772 which trace to this disaster.

It was not until after Braddock's defeat in July, 1755, that the Virginia Frontier was threatened by incursions of parties of French and Indians, but they were continuously in danger for many years following, especially in the spring and fall. George Washington was aware of the danger soon after he returned from Braddock's defeat.

At Fort Cumberland he wrote on July 18, 1755 to Governor Dinwiddie:

"I tremble at the consequences that this defeat may have upon our back settlers, who, I suppose, will all leave their habitations unless there are proper measures taken for their security." Thus began the long struggle to protect the settlers; a cause championed by Washington in charge of the militia of Virginia at Winchester, and a situation only slightly understood by Gov. Dinwiddie and the Virginia Assembly. The long struggle to give the frontier adequate protection, and the activities of the militia would make a voluminous book of interesting and valuable proportions. Forts were gradually built, but nothing that was done was adequate. Many people fled from their homes in the South Branch Valley in the fall of 1755 and there was no unbroken peace for many years.

The irony in the building of Braddock's Road to the west to meet the French is well described by Reuben Gold Thwaites:

"Braddock's road, laboriously cleared through the wilderness to reach the French and Indians now proved equally convenient to the latter as a pathway to the English border." Dunas had often six or seven war parties out at a time "always accompanied by French-men."

Among the records of forts, militia and attacks, Washington and other militia officers mention both Upper Tract and Fort Seybert, either by location, or by name, as well as other on the South Branch and the South Fork.

In August 1756 Washington wrote to Gov. Dinwiddie saying "we have built some forts and altered others as far south on the Potomac as settlers have been molested, and there remains one body of inhabitants at a place called Upper Tract who need a guard. Thither I have ordered a party. ***

Beyond this, if I am not misinformed there is nothing but a continued series of mountains uninhabited until we get over to the waters of the James River, not far from the fort which takes its name from your Honor; and thence to May River.

Buidling the forts did not give the people a feeling of safety, for in November 1756 Washington wrote further to Gov. Dinwiddie, in a plea for more adequate protection as follows:

"In short, they (inhabitants) are so affected with approaching ruin that the whole back country is in a general motion toward the other colonies; and I expect that scarce a family will inhabit Frederick, Hampshire or Augusta county in a little time."

Washington was opposed to the plan for the building of a chain of small forts, and preferred to have several strong forts, well garrisoned, with companies of Rangers going out from them. However, he presented a plan for the forts (23), as the Assembly favored, in November 1756 at which time he said: "Besides most of the forts are already built by the country people or soldiers, and require but little improvement save one or two, as Dickinson's and Cox's."

If Forts Upper Tract and Seybert were over garrisoned the garrison must have been removed, for on September 1, 1937 [sic], after five people had been killed and eight captured on the Branch, Major Andrew Lewis, who had been ordered to regulate the militia of Augusta County, wrote to George Washington:

"There is one place yt (yet) vacant which is not garrisoned. Ye consequences may be bad, that is ye So. Branch or So. Fork Between Capt. Woodward's old Station and Preston's (Capt. Preston was stationed in the Bullpasture) as ye governor has not given me a Direct Answer nor I Believe wont I am afraid that place must be Deserted."

How bad the consequences were the following April is appreciated only slightly, even by those familiar with the published records and traditional stories of the surprise attack on Fort Seybert on a foggy morning when a number of the men were away from the vicinity, having gone across the mountain on business. Waddell says that there was a shortage of ammunition in the fort. Capt. Seybert surrendered to the unfaithful promises of the Indians in the hope of saving the lives of the people in the fort. No censure or blame should be placed on him for what he did in the hope of safety. Following the surrender came the massacre of seventeen people; the capture of upwards of twenty-four, and the burning of the fort.

Six days after this happened, on the 4th of May 1758, Washington wrote to John Blair (then acting Governor of Virginia) from Fort Loudoun (Winchester) to tell him of the disasters:

"The enclosed letter from Capt. Waggener will inform your Honor of a very unfortunate affair. From the best accounts I have yet been able to get there are about 60 persons killed and missing. Immediately upon receiving this Intelligence I sent out a Detachment of the Regiment, and some Indians that were equipped for war (Indians were in the employ of the colonists as well as the French) in hopes of their being able to intercept the Enemy in the retreat. I was fearful of this stroke, but had not time enough to avert it, as your Honor will find by the following account which came to hand just before Capt. Waggener's letter, by Capt. Mackenzie."

The notes on this report are that Lieutenant Gist with six soldiers and 30 Indians marched the 2nd of April from the South Branch towards Fort Duquesne. After a tedious march, occasioned by deep snows on the mountains, they got on the waters of the Monongahela, where Mr. Gist was lamed by a fall from a steep bank and rendered incapable of marching. Some of the party stayed with him and the rest, all Indians, divided themselves into three parties and separated. Ucahala and two others found a large Indian Encampment about fifteen miles on "this side" of Ft. Duquesne. From the size of it and the number of tracks they judged it to be at least 100, making directly for the frontiers of Virginia, as they again discovered by crossing their tracks. After the parties had joined, and were marching in, Lieutenant Gist came upon the tracks of another large party pursuing the same course.

Undoubtedly, among these were the Indians who perpetrated the massacres at Forts Upper Tract and Seybert some days later, before Washington could send aid to the people.

There is more to be learned from official records and reports of these incidents and revealing information is gradually being uncovered.

The Roger Dyer Family Association is planning to erect a monument at the grave of the victims of the Fort Seybert massacre, five of whose names are known. It is hoped that the residents of the South Branch and South Fork Valleys, as well as all others interested in dignifying their historic past, and honoring the memory of the early settlers, whose difficulties were so overwhelming, may encourage the undertaking.