From the formation of the earliest communities, sectionalism developed between western and eastern Virginia. The Virginia State Constitution, adopted in 1776, granted voting rights only to white males owning at least 25 acres of improved or 50 acres of unimproved land. This reflected the interest of eastern Virginia, discriminating against the emerging class of small land owners in western Virginia. Furthermore, the constitution delegated a disproportionate representation in the state General Assembly to eastern Virginia by allowing only two delegates per county, regardless of population. Only four of the state's twenty-four senate districts were west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In a letter to the Richmond Examiner in 1803, under the pseudonym "A Mountaineer", Harrison County delegate John G. Jackson condemned both the property qualifications and the unbalanced representation. Because only white men who owned land were allowed to vote and many western Virginians did not own the land on which they lived, they did not have the right to vote. In 1816, Thomas Jefferson called for representation based on white population, free white male suffrage, and popular election of state and local officials.

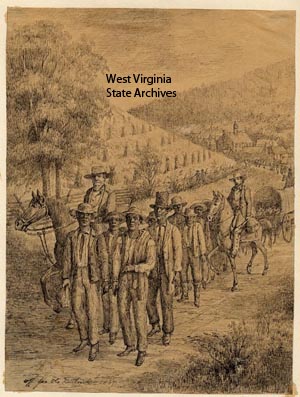

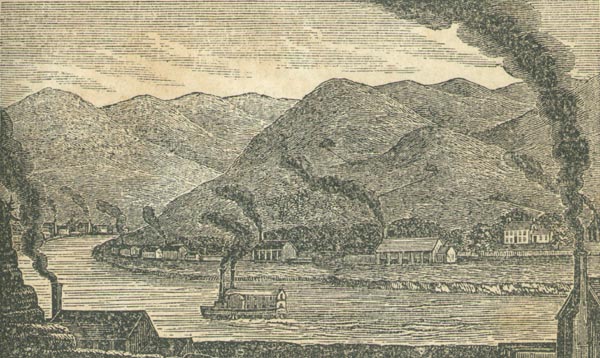

| Delegates from the Shenandoah Valley and regions westward attended conventions held in Staunton in 1816 and 1825. In general, these failed to produce any long-term answers to the problems. In response to the earlier conventions, the Virginia General Assembly passed a number of acts for the benefit of western Virginia. The reapportionment of the Senate based upon white population gave the western region greater representation. Previously, representation was based on total population, including slaves. Due to the large slave population of eastern Virginia and the general absence of slaves in western Virginia, representation in the General Assembly favored the East. In response to western demands, a Board of Public Works was created to legislate internal improvements, providing hope of developing more roads and canals in the West. The General Assembly also established the first state banks in western Virginia at Wheeling and Winchester. |  Sketch by Joseph H. Diss Debar Diss Debar Collection (Ph79-191) |

|

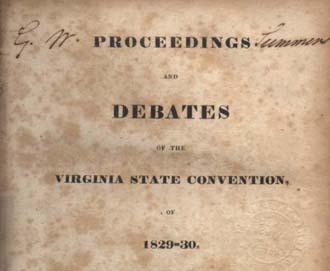

In 1828, western demands for reform led to passage of a popular referendum on a constitutional convention. The constitutional convention of 1829-1830 opened in Richmond on October 5, 1829, attended by such prominent Virginians as James Madison, James Monroe, John Marshall, and John Tyler. Western demands for free white male suffrage, representation based on white population, and the direct election of state and local officials were not met, as eastern Virginia conservatives defeated virtually every major reform. Statewide, the new constitution was approved by a margin of 26,055 to 15,566, although voters in present-day West Virginia rejected it 8,365 to 1,383. Calls for secession began immediately, led by newspapers such as the Kanawha Republican. |

Over the next twenty years, the General Assembly eased some of this sectional tension. Nineteen new western counties were organized, giving the region greater representation. A number of internal improvements were made in the West, including the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike and the Northwestern Turnpike.

| In 1831, the issue of African Americans came to the forefront following Nat Turner's raid, which killed sixty-one whites in Southhampton County, Virginia. That same year, William Lloyd Garrison first printed his newspaper, The Liberator, marking the beginning of an organized national movement to end slavery, called abolitionism. Some abolitionists disapproved of slavery on a moral basis. Others, including prominent western Virginia political leaders, supported abolitionism because they felt slaves were performing jobs white laborers should be paid to do. Washington College President Henry Ruffner, the son of Kanawha Valley salt industry pioneer David Ruffner and a slaveholder himself, wanted to end slavery in trans-Allegheny Virginia in order to provide more paying jobs for white workers. He outlined this theory in an address delivered to the Franklin Society in Lexington, Virginia, in 1847. His speech, later printed in pamphlet form and distributed nationally, stated that slavery kept white laborers from moving into the Kanawha Valley. |  |

Massachusetts abolitionist Eli Thayer sought to demonstrate that free labor was superior to slave labor. He established an industrial town at Ceredo in Wayne County, beginning in 1857. The laborers, white New England emigrants, were all paid for their work. The experiment failed when some investors were unable to contribute and a national economic depression restricted the availability of additional money.

|

In 1850, the year that Congress adopted extensive compromises to ease the growing tensions between North and South in the country, Virginia delegates once again met in Richmond to settle problems between East and West in the constitutional convention of 1850-1851. Several of these delegates to what was called the Reform Convention rose to political prominence, including Joseph Johnson (the first Virginia governor from Trans-Allegheny Virginia), Charles J. Faulkner, Gideon D. Camden, John Janney, John S. Carlile, Waitman T. Willey, Benjamin Smith and George W. Summers. Eastern Virginia conservatives reached agreement with the West on the major issues remaining from the 1829 convention. All white males over the age of twenty-one were given the right to vote regardless of whether they owned property. The convention also approved the election of the governor and judges by the people. Delegates, including many from western Virginia, agreed to a provision allowing for property to be taxed at its total value, except for slaves, who would be valued at rates well below their actual worth. |

| Over the next few years, the state government tried to gain support from western Virginia by completing various internal improvements. However, the 1857 national depression defeated these efforts to improve western Virginia's economy. The salt industry in the Kanawha Valley gradually collapsed. Mills and factories throughout all of present-day West Virginia were forced to close. Yet, due to the 1850 Constitution, eastern and western Virginians seemed closer politically than they had been at any time in history. |

|

|

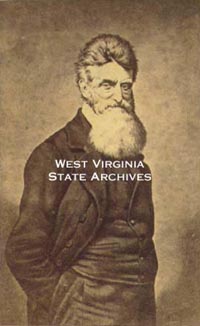

On October 16, 1859, abolitionist John Brown and his followers, determined to establish a colony for runaway slaves in Virginia, launched a raid on the United States Armory and Arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Brown and his men were successful in seizing the armory, but news of the raid got out, and they were forced to withdraw into an engine house, where the surviving members were captured on October 18. Brown's raid brought national attention to the emotional divisions concerning slavery, and when he was hanged on December 2, he was mourned as a martyr by many in the North, while Southerners were outraged by his acts. John Brown's raid brought emotions to a fever pitch, and was one of the key events on the road to a tumultuous civil war. This conflict would provide westerners the opportunity to break away from Virginia and form a new state. |